J Educ Community Health. 10(3):128-135.

doi: 10.34172/jech.2110

Original Article

Subjective Well-Being and Its Relationship With Personality Traits, Irrational Beliefs, and Social Support: A Model Test

Sevil Momeni Shabani 1, *  , Gülendam Oya Ersever 2, Fatemeh Darabi 3

, Gülendam Oya Ersever 2, Fatemeh Darabi 3

Author information:

1Psychological Counseling and Leadership Group, Department of Educational Sciences, Faculty of Education, Istanbul Kültür University, Istanbul, Turkey

2Department of Educational Sciences, Faculty of Education, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey

3Department of Public Health, Asadabad School of Medical Sciences, Asadabad, Iran

Abstract

Background: Considering the change in the life situation during the student period, attention to their health, especially the subjective well-being of students, is of particular importance. Social support is very important in this era and the aim of this study is to examine a model between subjective well-being and personality traits and irrational beliefs with the mediation of social support.

Methods: The statistical population included all the students of Hacettepe University in Turkey, and 296 people were selected as a sample using a multi-stage random method. To measure subjective well-being, social support, personality traits and irrational beliefs, Subjective Well-Being Scale (Tuzgöl Dost, 2005a); Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS) (Yıldırım, 2004); Adjective-Based Personality Test (Bacanlı, İlhan, & Aslan, 2009) and the Irrational Beliefs Scale Short Form (Türküm, 2003) scales were used, respectively, which were psychologically conducted in Turkey for Turkish samples and had good validity and reliability.

Results: The model test through structural equations showed that there is a significant relationship between neuroticism and conscientiousness both directly and indirectly through social support and subjective well-being. In this model, the indirect relationship of agreeableness with subjective well-being through social support was significant, but extroversion, interpersonal communication, and relational self-perception could not show a significant relationship through the mediation of social support on subjective well-being.

Conclusion: Neuroticism and conscientiousness are both directly and indirectly related to subjective well-being through social support. The indirect relationship of agreeableness with subjective well-being was confirmed through social support, but extroversion and interpersonal communication and self-view showed a direct relationship with well-being and the mediation of social support was not confirmed in their case.

Keywords: Subjective well-being, Personality traits, Irrational beliefs, Social support

Copyright and License Information

© 2023 The Author(s); Published by Hamadan University of Medical Sciences.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Please cite this article as follows: Momeni Shabani S, Ersever GO, Darabi F. Subjective well-being and its relationship with personality traits, irrational beliefs, and social support: a model test. J Educ Community Health. 2023; 10(3):128-135. doi:10.34172/jech.2110

Introduction

In all societies, students are an important group whose physical, mental, and social health is of great importance. Entering a university means starting a dynamic transition period (1), but many mental health problems have been reported in this period (2-4). These problems, on the one hand, endanger the general health of the students (2) and, on the other hand, cause a drop in academic performance, leading to adverse consequences such as dropout (3). In such a situation, it is necessary to place special importance on their mental health (4).

Subjective well-being is one of the important pillars of mental health, and overlooking it may bring about various mental illnesses for students because important aspects such as the meaning of life (5) and establishing compliance with new situations (6,7) are provided in the shade of optimal subjective well-being.

Subjective well-being refers to a range of mental phenomena from a person’s overall satisfaction with life to pleasant and unpleasant feelings and satisfaction in specific areas such as career, leisure time, and marriage. Subjective well-being includes two emotional components and one cognitive component. People with a strong sense of subjective well-being experience more positive emotions and have a positive self-evaluation of the surrounding events, while those with a low level of well-being perceive events and their life situations as unfavorable and experience more negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, anger, and suicide (8,9). Many variables are related to subjective well-being, including personality type (10), social support (11), and irrational thinking (12).

Given that social support has a high capacity for change, this study examined a model regarding the effect of personality traits and irrational beliefs on subjective well-being via the mediating effect of social support.

Five big personality traits have been defined by Goldberg as follows:

-

Extraversion includes such traits as being interested in social presence, talking a lot, seeking excitement, enjoying the company of others, and being full of energy.

-

Openness to experience includes such traits as being curious, being adventurous, looking for new ideas, and being creative.

-

Conscientiousness includes such attributes as conscientiousness, regularity, and high efficiency.

-

Agreeableness includes such attributes as trusting others, being friendly, and exhibiting friendly behavior.

-

Neuroticism includes such traits as hot temperament, vulnerability to the behaviors of others, the lack of emotional stability, and anxiety (13).

Irrational beliefs are demands that appear as mandatory preferences, and if they are not fulfilled, they cause anxiety, confusion, and low social performance in people. The belief that there is no justice in the world, which can be used as a generalization, is an example of irrational belief. This specific one is called excessive (14).

Any kind of help to others to deal with biological, psychological, and social stress is called social support. Support may come from an individual or community such as family members, friends, neighbors, religious institutions, colleagues, caregivers, or support groups. It may take the form of practical support (e.g., doing household chores, offering advice), tangible support (e.g., giving money or other direct material assistance), and/or emotional support which allows the individual to feel valued, accepted, and understood (15).

It is obvious that the meaningfulness of the model can be used as a guide in improving the subjective well-being of students in planning to improve their mental health. The present study aimed to determine the level of students’ well-being, social supports, personality traits, and irrational beliefs to test the hypothesis about the mediating role of social support in the relationship between subjective well-being and personality traits as well as irrational beliefs.

Materials and Methods

Structural equation modeling (SEM) is more powerful than other multivariate statistical methods that test the relationships between more than one variable (16). In addition, it was decided to use SEM since the variables examined were of both observed and implicit types, and we know that SEM is suitable for variables of all natures. This study was carried out using data collected from 296 undergraduate students studying at various faculties of Hacettepe University. The statistical population included all the students of Hacettepe University in Turkey, of which 296 students were sampled by the multi-stage random method.

The random stratified technique was used to sample students from various faculties of Hacettepe University based on the type of faculty and field of study. Sampling from each class was randomly based on a list of student numbers. After randomly selecting the sample from the list, if the student was willing to participate in the study, he or she was included in the project to fill out the questionnaire; otherwise, the next person was selected from the list of students.

The inclusion criteria were being a university student and being present in the classroom when completing the questionnaire. The exclusion criteria were rejecting the invitation to participate in the program and postponing the completion of the questionnaire for times other than attending the class.

Data Collection Tools

Various measurement tools were used to measure the variables in the present study, including: Subjective Well-Being Scale (SWBS) (17); Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS) (18); Adjective-Based Personality Test (ABST) (19) and the Irrational Beliefs Scale Short Form (IBSSF) (20) scales. Information on the psychometric properties of the measurement tools used in this study is given below.

Subjective Well-Being Scale

The 46-item Subjective Well-Being Scale (SWBS) (17) determines the well-being of individuals based on the frequency and intensity of experiencing positive and negative emotions, based on individuals’ cognitive evaluations of their lives. This measurement tool includes various personal expressions related to the areas of life expressed as positive and negative. This scale is a Likert type scale graded between 1-5. The scale includes 26 positive and 20 negative statements. Items 2, 4, 6, 10, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21, 24, 26, 28, 30, 32, 35, 37, 38, 40, 43 and 45 are negatively worded items. Reverse scoring is done for negative statements. The highest score to be obtained from the 46-item scale is 230) and the lowest score is 46. An increase in the scale score is interpreted as having a high subjective well-being. The Cronbach Alpha reliability coefficient calculated by using the 46 items obtained from the factor analysis and the data in this application was determined as 0.903 (17).

Perceived Social Support Scale

In this study, the Perceived Social Support Scale (PSRS-R) revised by Yıldırım (18) was used. This scale was first developed by Yıldırım and then revised by the author himself in another study. The scale, which includes 50 items in total, consists of three factors: “Family Support (FS)”, “Friend Support (FrS)”, and “Teacher Support (TS). Items 17, 29, and 44 in the scale are the only negative statements included in the FS, and these items are related to the dimensions of my family, friends, and teachers, respectively. Negative items were scored inversely. An increase in the scores obtained from the scale is interpreted as an increase in the level of perceived social support. Alpha=0.91, rxx= 0.85 for all family social support scale (FSSS) ; Alphaa = 0.93, rxx = 0.86 for teacher social support scale (TSSS). According to these results, it can be said that the scores obtained from the FSSS and its subscales are reliable, and that these scales can be used safely to measure the social support that students receive from various sources, including family, friends and teachers (18).

Adjective-based Personality Test

This measurement tool was developed by Bacanlı, İlhan, and Aslan (19) and is a Likert-type scale containing 40 adjective pairs scored between 1 and 7. ABST includes 5 factors and these factors are named as extraversion, agreeableness, responsibility, emotional instability and openness to experience. Items 2.7.12.17.22.27.32.37.39 items Extraversion, 3.8.13.18.23.28.33.36 items Openness to Experience, 4.9.14.19.24.29.34.38.40 items agreeableness/agreeableness and 5.10.15.20 Articles.25.30.35 explain the dimension of Responsibility. The lowest internal consistency coefficient calculated for the sub-dimensions of Adjective-Based Personality Test (ABST) was 0.73; it is seen that the highest coefficient is 0.89. The reliability coefficients in the context of stability obtained by the test-retest method are higher than the 0.70 coefficient, which is accepted as a criterion. Based on this, it can be said that the scores obtained from the ABST are reliable (19).

Irrational Beliefs Scale Short Form

In this study, the 15-item Irrational Beliefs Scale-Short form (IBSSF), developed by Türküm (20), was used to measure participants’ irrational beliefs. The scale consists of three dimensions called “need for approval”, “interpersonal relations” and “me”. This scale is a Likert-type scale rated between 1 and 5, and an increase in scores is interpreted as an increase in irrational beliefs, and a decrease in a decrease in these beliefs. The reliability of the 15-item scale was examined by the application of Cronbach’s Alpha and test-retest methods. In addition to the reliability methods, item-total test correlations of the items were also evaluated. It was stated that these correlations ranged between 0.50 and 0.52, and the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was 0.75 for the overall scale. The correlation of the scores obtained from the two applications performed ten weeks apart was calculated as 0.81 (20).

Data for the research were collected by the researcher in charge of data collection in the classroom by administering the scales to the volunteer students. The participants have already been given instructions on the purpose of the research, how to respond to the scales, and the fact that the information obtained from the scales will be used within the scope of a scientific study, so they did not need to provide any identifying information. It took 45-55 minutes to fill out the questionnaire. The data obtained from the participants were transferred to the computer environment. First of all, descriptive statistics (minimum, maximum, mean, and standard deviation) were calculated to determine the level of subjective well-being, personality, irrational beliefs, and social support. The Pearson correlation coefficient was then used to determine the relationships between the variables and their sub-dimensions. Then, confirmatory factor analysis was calculated through the AMOS 18.0 software suite to determine the extent to which the values obtained from the sub-scores of the scales accounted for the total score. Afterward, the confirmatory factor analysis was performed for personality (five sub-dimensions), irrational beliefs (three sub-dimensions), and social support (three sub-dimensions). The research also employed SEM since it aimed to examine the mutual and complex relationships between more than one variable and to test a model with more than one variable. Moreover, to determine the participants’ subjective well-being levels, three different models were created, and the results were interpreted by testing the models.

Results

In terms of the gender distribution of the samples, there were 219 girls (74%), 76 boys (25.7%), and one missing person. In terms of the distribution of the Hacettepe participants among different faculties, 91 people were in the Faculty of Education (30.74%), 49 people in the Faculty of Fine Arts (16.6%), 75 people in the Faculty of Literature (25.3%), 79 people in the Faculty of Engineering (26.7%), and 2 people were missing. Regarding age, 10 people were 17 years old (3.3%), 96 people were 18 years old (32.4%), 89 people were 19 years old (30%), 52 people were 20 years old (17.5%), 15 people were 21 years old (5.06%), 8 people were 22 years old (2.7%), 9 people were 23 years old (3.04%), 6 people were 24 years old (2.02%), 5 people were 25 years old (1.68%), 4 people were 26 years old (1.35%), and 2 people were 27 years old (.68%).

Evaluation of the Hypothetical Model Developed within the Scope of the Research

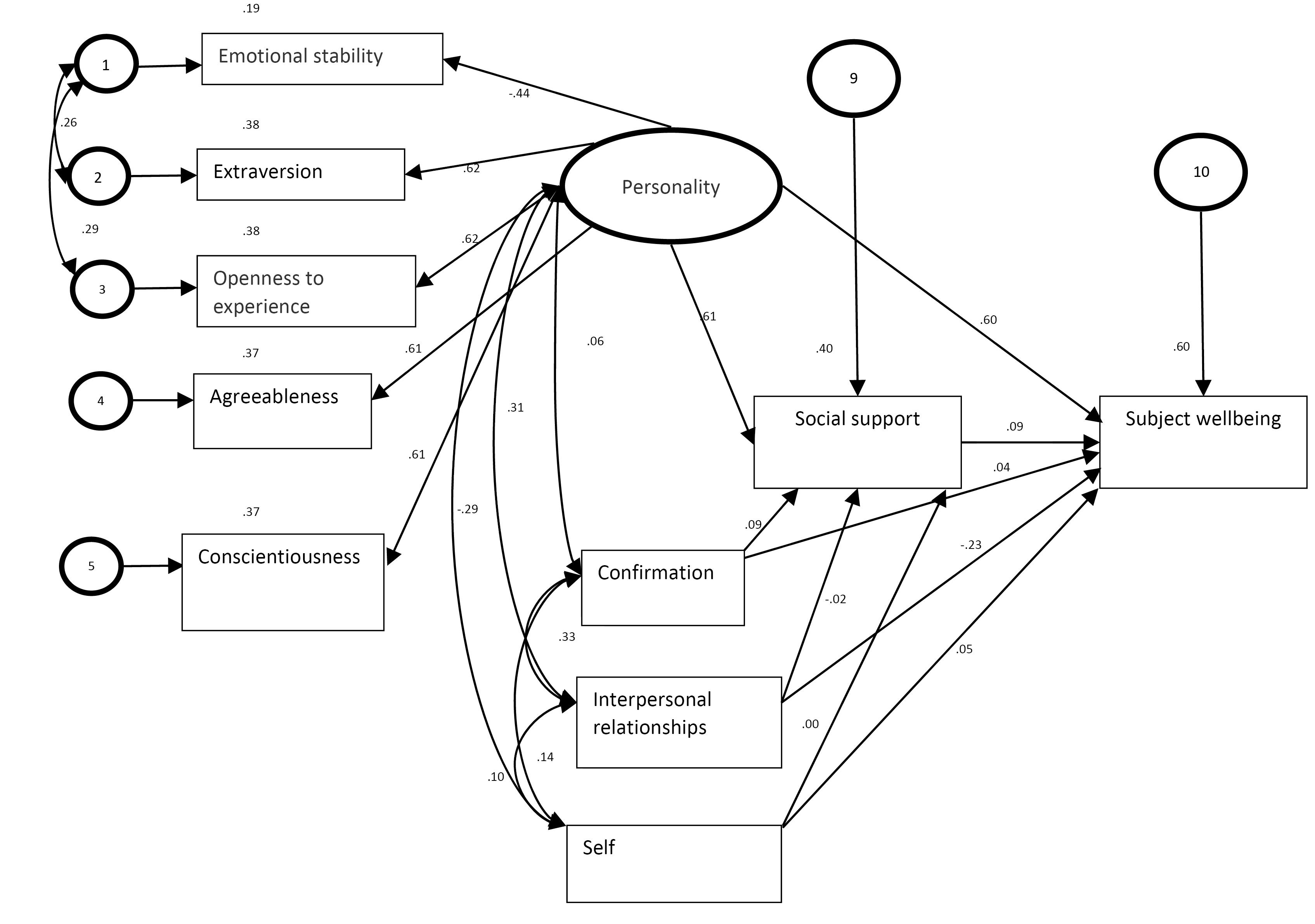

First of all, to determine the extent to which the subjective well-being of the participants was explained by their social support perceptions and personality traits, a model was created with five personality traits and three sources of social support and was subjected to path analysis. Figure 1 displays the path diagram created by the analysis.

Figure 1.

The First Model Created to Explain the Subjective Well-Being of the Students

.

The First Model Created to Explain the Subjective Well-Being of the Students

The model established to explain the students’ subjective well-being is depicted in Figure 1. The total scores of personality were included in the model as latent and the social support scores as observed scores in the model. In addition, the relationships between social support and personality traits were defined. Table 1 presents the values obtained from the calculations.

Table 1.

Values Calculated in the First Model Created to Explain Subjective Well-Being Levels (N = 296)

|

Relationships

|

Non-standardized

Coefficients

|

Standardized

Coefficients

|

P

Value

|

| Personality- Social support |

1.64 |

0.61 |

0.001 |

| Confirmation- Social support |

0.33 |

0.09 |

0.07 |

| Interpersonal relationships- Social support |

-0.06 |

-0.01 |

0.76 |

| Self-social support |

-0.0009 |

-0.002 |

0.97 |

| Personality- Conscientiousness |

1.00 |

0.60 |

0.001 |

| Personality- Agreeableness |

0.94 |

0.61 |

0.001 |

| Personality- Openness to experience |

0.97 |

0.61 |

0.001 |

| Personality- Extroversion |

0.99 |

0.61 |

0.001 |

| Personality- Neuroticism |

-0.60 |

-0.43 |

0.001 |

| Personality- Subjective wellbeing |

2.28 |

0.60 |

0.001 |

| Social support- Subjective wellbeing |

0.16 |

0.09 |

0.11 |

| Self- Subjective wellbeing |

0.41 |

0.04 |

0.29 |

| Interpersonal relationships- Subjective wellbeing |

-1.51 |

-0.23 |

0.001 |

| Agreeableness- Personality |

0.23 |

0.03 |

0.001 |

According to Table 1, affirmation, self, and interpersonal relations could not significantly account for social support, and there were no relationships between these variables (P > 0.05). It was also found that social support and self-beliefs did not significantly explain the participants’ subjective well-being levels (P > 0.05). On the other hand, It was found that personality traits significantly explain social support (R2 = 0.61; P < 0.05). Similarly, the students’ subjective well-being levels were significantly explained by the students’ personality traits (R2 = 0.60; P < 0.05). Therefore, there were both significant and non-significant relationships in the model, which is the reason for the low model-data fit indices (χ2/sd = 5.13; RMSEA = 0.11, CFI = 0.87; IFI = 0.87; GFI = 0.92). In this regard, non-significant relationships were removed from the model, and a new model was created. The path diagram resulting from the calculation of the newly created model is presented in Figure 2.

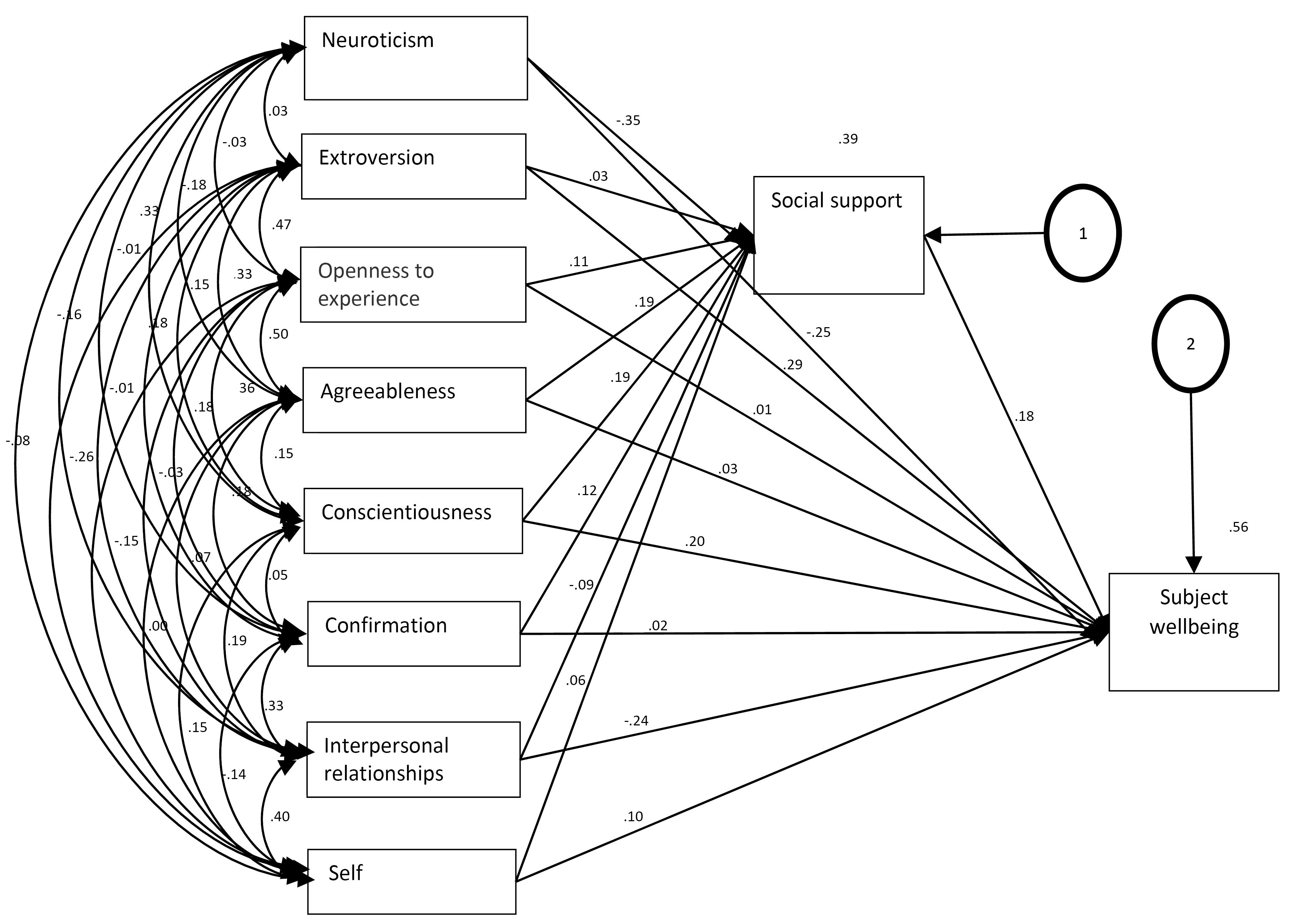

Figure 2.

The Second Model Created to Explain the Subjective Well-Being of the Students

.

The Second Model Created to Explain the Subjective Well-Being of the Students

As seen in Figure 2, the new model was created with the observed variables. Table 2 presents the values calculated for the model created with the direct and indirect relationships to explain the participants’ subjective well-being level.

Table 2.

Values Calculated in the Second Model Created to Explain Subjective Well-Being Levels (N = 296)

|

Relationships

|

Non-standardized

Coefficients

|

Standardized

Coefficients

|

P

|

| Neuroticism- Social support |

-0.66 |

-0.34 |

> 0.001 |

| Extroversion- Social support |

0.04 |

0.02 |

0.63 |

| Openness to experience-Social support |

0.19 |

0.11 |

0.051 |

| Agreeableness- Social support |

0.32 |

0.18 |

> 0.001 |

| Conscientiousness- Social support |

0.31 |

0.19 |

> 0.001 |

| Confirmation- Social support |

0.43 |

0.12 |

0.16 |

| Interpersonal relationships- Social support |

-0.33 |

-0.09 |

0.08 |

| Self- Social support |

0.28 |

0.05 |

0.23 |

| Interpersonal relationships- Subjective wellbeing |

1.52 |

-0.23 |

> 0.001 |

| Confirmation- Subjective wellbeing |

0.11 |

0.01 |

> 0.66 |

| Conscientiousness- Subjective wellbeing |

0.57 |

0.19 |

> 0.001 |

| Agreeableness- Subjective wellbeing |

0.10 |

0.03 |

0.50 |

| Openness to experience- Subjective wellbeing |

0.03 |

0.01 |

0.81 |

| Extroversion- Subjective wellbeing |

0.85 |

0.28 |

> 0.001 |

| Neuroticism- Subjective wellbeing |

-0.86 |

-0.25 |

> 0.001 |

| Social Support- Subjective wellbeing |

0.32 |

0.18 |

> 0.001 |

| Self- Subjective wellbeing |

0.86 |

0.09 |

0.01 |

According to Table 2, there are significant and non-significant relationships similar to the first model. Extraversion, openness to experience, personality traits, approval, interpersonal relationships, and self-beliefs did not significantly explain the social support mediator variable (P > 0.05). However, it was observed that extraversion is the best variable in accounting for the participants’ subjective well-being levels (R2 = 0.28; P < 0.05). It was revealed that the second model does not provide model-data fit because the variables in the model did not meet the linearity assumption. Similarly, by removing the non-significant relationships in the model, the final model was created, and calculations were carried out. Figure 3 depicts the path diagram created as a result of the calculations.

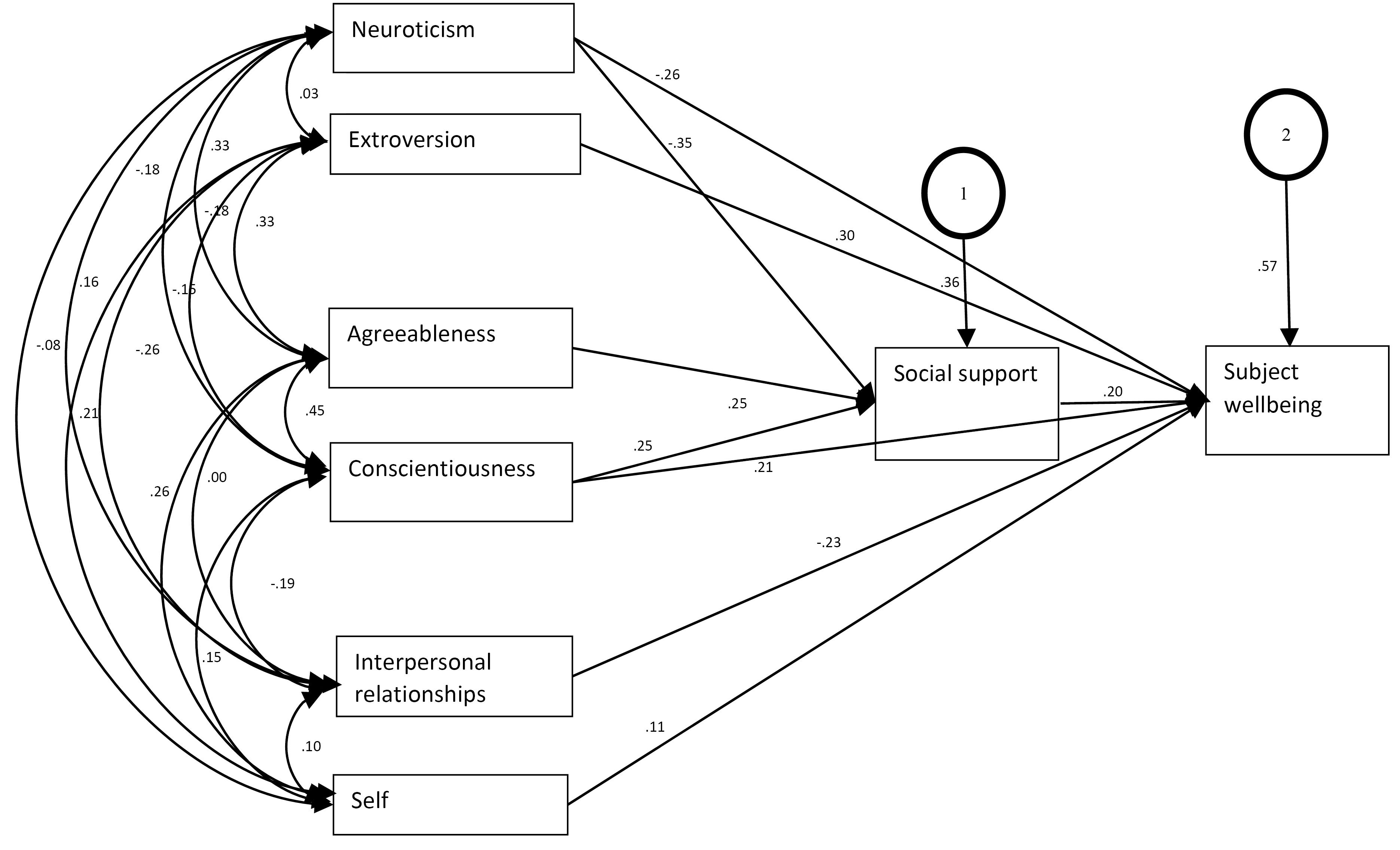

Figure 3.

The Final Model Created to Explain the Subjective Well-Being of the Students

.

The Final Model Created to Explain the Subjective Well-Being of the Students

Based on Figure 3, the final model was developed by eight observed variables. In the last model, subjective well-being was defined as the dependent variable, social support as the mediator variable, and emotional stability, extraversion, agreeableness, responsibility, interpersonal relations, and self variables as the independent variables. The values resulting from the calculations are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Values Calculated in the Final Model Created to Explain Subjective Well-Being Levels (N = 296)

|

Relationship

|

Non-standardized Coefficients

|

Standardized

Coefficients

|

P

Value

|

| Neuroticism- Social support |

-0.66 |

-0.34 |

< 0.001 |

| Agreeableness- Social support |

0.43 |

0.25 |

< 0.001 |

| Conscientiousness- Social support |

0.40 |

0.24 |

< 0.001 |

| Interpersonal relationships- Subject wellbeing |

-1.45 |

-0.22 |

< 0.001 |

| Conscientiousness- Subject wellbeing |

0.61 |

0.21 |

< 0.001 |

| Extroversion-Subject wellbeing |

0.88 |

0.30 |

< 0.001 |

| Neuroticism- Subject wellbeing |

-0.86 |

-0.25 |

< 0.001 |

| Social support- Subject wellbeing |

0.34 |

0.19 |

< 0.001 |

| Self- Subject wellbeing |

0.91 |

0.10 |

0.009 |

Table 3 shows that all relationships in the final model were significant (P < 0.05). Emotional instability (R2 = -0.34; P < 0.05), compatibility (R2 = 0.25; P < 0.05), and responsibility (R2 = 0.24; P < 0) of social support defined as a mediator variable in the model were determined to be significantly explained by personality traits. Students’ subjective well-being levels were extraversion (R2 = 0.30; P < 0.05), emotional instability (R2 = -0.25; P < 0.05), interpersonal relationships (R2 = -0.22; P < 0.05), responsibility (R2 = 0.21; P < 0.05), and social support (R2 = 0.19; P < 0.05). Moreover, self (R2 = 0.10; P < 0.05) ) was found to be significantly explained by calculated values for the evaluation of model-data fit in the final model created, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Fit Values Calculated in the Last Model Created to Explain Subjective Well-Being Levels (N = 296)

|

Model Indices

|

X2

|

df

|

χ2/df

|

RMSEA

|

CFI

|

IFI

|

GFI

|

| Value |

7.28 |

4 |

1.82 |

0.05 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

Note. RMSEA: Root mean square error of approximation; CFI: Comparative fit index; IFI: Incremental fit index; GFI: Goodness-of-fit index.

Table 4 exhibits that the model-data fit of the final model is at a perfect level (21,22). Based on the results, there was a negative relationship between the students’ emotional instability levels and social support levels. Similarly, there was a negative relationship between subjective well-being and emotional instability and a positive relationship between the students’ adaptability and responsibility and their social support levels. Responsibility is a direct predictor of subjective well-being, while agreeableness explains subjective well-being through social support. At the same time, it was found that the subjective well-being levels of extroverted students are high. Furthermore, there was a negative relationship between beliefs about interpersonal relationships and subjective well-being, and this variable had a positive relationship with self-belief.

Discussion

The present study indicated that the personality traits of neuroticism, extroversion, conscientiousness, and agreeableness can improve subjective well-being through the mediation of social support, but other personality types could not show the mediating role of social support on subjective well-being. Furthermore, the direct effect of irrational beliefs on subjective well-being was observed in the present study, but social support could not mediate the relationship between subjective well-being and irrational beliefs.

Extraversion and responsibility as personality traits explain subjective well-being directly and positively. Emotional instability also explains subjective well-being directly but in a negative relationship. It was found that emotional instability, compatibility, and responsibility sub-dimensions of personality traits predict subjective well-being through the variable of social support. The literature review demonstrated that people’s personality traits are significant explanatory factors of their psychological/subjective well-being (23,24). In a study conducted by Eryılmaz and Öğuldu (25), extroversion, emotional instability, and conscientiousness were found to be among the five personality traits that significantly explain subjective well-being, which agrees with our results. Malkoç (26) observed that extraversion and conscientiousness as personality traits explain subjective well-being. Eryılmaz and Ercan (27) who carried out their study on different age groups reported that subjective well-being in the age group of 19-25 was explained by all personality traits (i.e., emotional instability, responsibility, compatibility, and extroversion) except openness to experience. In adults aged 26-45, only emotional instability and conscientiousness were found to be significant predictors of subjective well-being. In other words, as the age of the individuals increased, the personality traits that explained their subjective well-being changed. Contrary to all these research findings, the study conducted by Jovanovic (28) indicated that the subjective well-being of individuals is not significantly explained by personality traits.

It was also found that the students’ perceptions of social support significantly explain their subjective well-being levels both indirectly and as a mediator variable. The positive relationship obtained between the perception of social support and subjective well-being indicates that as the students’ levels of receiving social support increase, their subjective well-being tends to increase as well. In Gouders et al’ s study, the relationship between mental well-being and social support was well established (11).

We found that the irrational beliefs of interpersonal relationships and self-beliefs significantly explain subjective well-being. On the other hand, it was determined that the need for validation belief was not a significant predictor of subjective well-being. In this direction, it was displayed that the belief in interpersonal relationships explains subjective well-being negatively and self-belief positively. Many researchers have considered irrational beliefs as a whole and reported that these behaviors are a negative predictor of subjective well-being (29,30).

People’s emotions and thought structures are essentially in interaction. Individuals begin to feel something the way they think about it. In this regard, it can be said that thoughts direct people’s lives in a significant way because people’s reactions are also shaped by the things and situations they think and especially feel. Conversely, one of the most effective ways of coping with the emotional difficulties and troubles experienced by people is to channel their thoughts in a good direction. In line with all this information, individuals’ irrational beliefs and thoughts will expectedly affect their emotions negatively. In the study carried out by Hamarta et al (31), the decrease in irrational beliefs increased problem-solving behaviors. Göller (32) also revealed that irrational beliefs are negatively related to academic achievement. The effect of social support on subjective well-being can be seen in such crises as the COVID-19 pandemic, which has been significantly effective in improving subjective well-being, enhancing positive emotions, and reducing negative emotions (33).

There is more robust documentation about the effect of social support on subjective well-being, and research on the details of social support to improve the well-being of students is one of the new research topics in this field (34). Personality traits and their impact on subjective well-being have also been demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic, and for this reason, the factor of personality traits should be considered in providing support during crises (35). The role of irrational beliefs in subjective well-being has been well clarified through the creation of emotional consequences and the impact on negative emotions (36).

As a result of this study, the fact that irrational beliefs are inversely related to subjective well-being shows the effect of thoughts on emotions. The findings are in agreement with many published studies and provide a good basis for future research on subjective well-being in students.

Conclusion

Neuroticism and conscientiousness are both directly and indirectly related to subjective well-being through social support. The indirect relationship between agreeableness and subjective well-being was confirmed through social support, but extroversion, interpersonal communication, and self-view showed a direct relationship with well-being, and the mediation of social support was not confirmed. It was also found that the students’ perceived social support is a significant and positive predictor of their subjective well-being levels. With the education programs that can be prepared in this direction, the social support provided to the students by the teachers, friends, and family can be increased. The present study provides suitable data for designing and implementing experimental studies on the methods of improving the subjective well-being of students as well as its effect on academic achievements in the future. Moreover, psychology counseling and guidance units of universities can foster good inter-departmental cooperation to promote the subjective well-being of students and their academic achievement, which requires research to investigate the effectiveness of inter-departmental interventions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the professors and staff of the Department of Counseling and Leadership Psychology in the Faculty of Humanities Education, Hacettepe University, who provided comprehensive support in the implementation of this research. In addition, we would like to express our sincere thanks to all the professors and students who cooperated in completing the questionnaire.

Authors’ Contribution

Methodology: Sevil Momeni Shabani.

Investigation: Gülendam Oya Ersever.

Validation: Gülendam Oya Ersever.

Writing–original draft: Fatemeh Darabi.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical Approval

The research was registered with an Ethics Code of 76000869/433-20722 and a code design of 1159 by the Ethics Committee at the Hacettepe University of Turkey.

Funding

No financial support was received to implement this research.

References

- Can G, Ozdilli K, Erol O, Unsar S, Tulek Z, Savaser S. Comparison of the health-promoting lifestyles of nursing and non-nursing students in Istanbul, Turkey. Nurs Health Sci 2008; 10(4):273-80. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2008.00405.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jenkins PE, Ducker I, Gooding R, James M, Rutter-Eley E. Anxiety and depression in a sample of UK college students: a study of prevalence, comorbidity, and quality of life. J Am Coll Health 2021; 69(8):813-9. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2019.1709474 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Medlicott E, Phillips A, Crane C, Hinze V, Taylor L, Tickell A. The mental health and wellbeing of university students: acceptability, effectiveness, and mechanisms of a mindfulness-based course. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18(11):6023. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18116023 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, Maj M, Maselko J, Phillips MR. No health without mental health. Lancet 2007; 370(9590):859-77. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61238-0 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Xie X, Zou B, Huang Z. [Relationships between suicide attitudes and perception of life purpose and meaning of life in college students]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 2012;32(10):1482-5. [Chinese].

- Li Z, Zhang J. Coping skills, mental disorders, and suicide among rural youths in China. J Nerv Ment Dis 2012; 200(10):885-90. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31826b6ecc [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Zhang J. Coping skill as a moderator between negative life events and suicide among young people in rural China. J Clin Psychol 2015; 71(3):258-66. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22140 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Heintzelman SJ, Kushlev K, Tay L, Wirtz D, Lutes LD. Findings all psychologists should know from the new science on subjective well-being. Can Psychol 2017; 58(2):87-104. doi: 10.1037/cap0000063 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lew B, Huen J, Yu P, Yuan L, Wang DF, Ping F. Associations between depression, anxiety, stress, hopelessness, subjective well-being, coping styles and suicide in Chinese university students. PLoS One 2019; 14(7):e0217372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217372 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Winzer R, Vaez M, Lindberg L, Sorjonen K. Exploring associations between subjective well-being and personality over a time span of 15-18 months: a cohort study of adolescents in Sweden. BMC Psychol 2021; 9(1):173. doi: 10.1186/s40359-021-00673-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Goudarz M, Foroughan M, Makarem A, Rashedi V. Relationship between social support and subjective well-being in older adults. Iran J Ageing 2015;10(3):110-9. [Persian].

- Spörrle M, Strobel M, Tumasjan A. On the incremental validity of irrational beliefs to predict subjective well-being while controlling for personality factors. Psicothema 2010; 22(4):543-8. [ Google Scholar]

- Angelini G. Big five model personality traits and job burnout: a systematic literature review. BMC Psychol 2023; 11(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s40359-023-01056-y [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Žeželj I, Lazarević LB. Irrational Beliefs. Eur J Psychol 2019; 15(1):1-7. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v15i1.1903 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- House JS, Umberson D, Landis KR. Structures and processes of social support. Annu Rev Sociol 1988; 14(1):293-318. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.14.080188.001453 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Chen J, Shirkey G, John R, Wu SR, Park H. Applications of structural equation modeling (SEM) in ecological studies: an updated review. Ecol Process 2016; 5(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s13717-016-0063-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Tuzgöl Dost M. Öznel iyi oluş ölçeği nin geliştirilmesi geçerlik güvenirlik çalışması. Türk Psikolojik Danışma ve Rehberlik Dergisi 2005; 3(23):103-111. [ Google Scholar]

- Yildirim İ. Algılanan sosyal destek ölçeğinin revizyonu. Eurasian J Educ Res. 2004(17):221-36.

- Bacanli H, İlhan T, Aslan S. Beş faktör kuramina dayali bir kişilik ölçeğinin geliştirilmesi: sifatlara dayali kişilik testi (SDKT). Türk Eğitim Bilimleri Dergisi 2009; 7(2):261-79. [ Google Scholar]

- Türküm AS. Akılcı olmayan inanç ölçeğinin geliştirilmesi ve kısaltma çalışmaları. Türk Psikolojik Danışma ve Rehberlik Dergisi 2003; 2(19):41-7. [ Google Scholar]

- Brown TA. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. Guilford Publications; 2015.

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2005.

- Akbari M. The role of personality traits and resiliency in prediction of nurses\’ psychological well-being. Int J Behav Sci 2014;7(4):307-13. [Persian].

- Sourati P, Farahani MN, Moradi A. The structural relation between personality traits, self-efficiency beliefs and subjective well-being among staff of Universities of Guilan. Int J Behav Sci 2014;8(1):37-45. [Persian].

- Eryilmaz A, Öğülmüş S. Ergenlikte öznel iyi oluş ve beş faktörlü kişilik modeli. Ahi Evran Üniversitesi Kırşehir Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi 2010; 11(3):189-203. [ Google Scholar]

- Malkoç A. Quality of life and subjective well-being in undergraduate students. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2011; 15:2843-7. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.200 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Eryilmaz A, Ercan L. Öznel iyi oluşun cinsiyet, yaş grupları ve kişilik özellikleri açısından incelenmesi. Türk Psikolojik Danışma ve Rehberlik Dergisi 2011; 4(36):139-49. [ Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic V. Personality and subjective well-being: one neglected model of personality and two forgotten aspects of subjective well-being. Pers Individ Dif 2011; 50(5):631-5. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.12.008 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ellis A, David D, Lynn SJ. Rational and irrational beliefs: a historical and conceptual perspective. In: David D, Lynn SJ, Ellis A, eds. Rational and Irrational Beliefs: Research, Theory, and Clinical Practice. Oxford University Press; 2010. p. 3-22.

- Ghanbari Hashemabadi BA, Garavand H, Dehghani Neyshaboori M. Goals prioritization, mental health and irrational beliefs of the students. J Appl Psychol Res 2014; 5(3):39-53. doi: 10.22059/japr.2014.52287.[Persian] [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hamarta E, Arslan C, Saygin Y, Özyeşil Z. Benlik saygısı ve akılcı olmayan inançlar bakımından üniversite öğrencilerinin stresle başaçıkma yaklaşımlarının analizi. Değerler Eğitimi Dergisi 2009; 7(18):25-42. [ Google Scholar]

- Göller L. Ergenlerin Akılcı Olmayan Inançları Ile Depresyon-Umutsuzluk Düzeyleri ve Algıladıkları Akademik Başarıları Arasındaki Ilişkiler. Erzurum: Yayınlanmamış Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Atatürk Üniversitesi; 2010.

- Huang L, Zhang T. Perceived social support, psychological capital, and subjective well-being among college students in the context of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asia Pac Educ Res 2022; 31(5):563-74. doi: 10.1007/s40299-021-00608-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lyu Y. A review of the influence of social support on the subjective well-being of college students. J Educ Humanit Soc Sci 2023; 8:1534-9. doi: 10.54097/ehss.v8i.4515 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kohút M, Šrol J, Čavojová V. How are you holding up? Personality, cognitive and social predictors of a perceived shift in subjective well-being during COVID-19 pandemic. Pers Individ Diff 2022; 186(Pt A):111349. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.111349 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Turner MJ, Miller A, Youngs H, Barber N, Brick NE, Chadha NJ. “I must do this!”: a latent profile analysis approach to understanding the role of irrational beliefs and motivation regulation in mental and physical health. J Sports Sci 2022; 40(8):934-49. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2022.2042124 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]