J Educ Community Health. 10(2):62-70.

doi: 10.34172/jech.2023.2289

Original Article

Psychosocial-Spiritual Factors Associated With Well-being of Older Population in Africa

Lawrence Clement Kehinde 1, *  , Aliya Saktaganovna Mambetalina 1, Baigabylov Nurlan Oralbaevich 1

, Aliya Saktaganovna Mambetalina 1, Baigabylov Nurlan Oralbaevich 1

Author information:

1Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Eurasian National University. L. N. Gumilyov Astana, Kazakhstan

Abstract

Background: The quality of well-being of the older population is a crucial determinant of successful aging as well as the achievement of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG target 3). However, the impact of psychosocial-spiritual factors on well-being is affected by the level of general health conditions in the older population. Previous studies have focused more on the physical health and psychological well-being nexus, but the role of general health conditions in mediating the association between psychosocial-spiritual factors and well-being in the older population in Africa was not investigated. This study, therefore, examined the psychosocial-spiritual factors associated with well-being in the older population in Africa with a focus to determine the contribution of all the psychosocial-spiritual factors when mediated by general health conditions.

Methods: In this regard, a quantitative research methodology was adopted using a descriptive survey. A total of 833 elderly people with a mean age of f 68.04±6.71 years were recruited, comprising 484 females and 399 males in five municipalities.

Results: The findings revealed that general health conditions, quality of life, social support, and social network are significantly associated with well-being in older people. Furthermore, the mediating effect of general health conditions had an inverse association with well-being.

Conclusion: Accordingly, a commitment to quality of life, healthcare services, social support, and family social network is effective for Africa to achieve healthy lives and promote well-being for individuals of all ages.

Keywords: Coping efficacy, Older people, Quality of life, Religiosity, Self-esteem, Social integration, Social network, Social supports, Well-being

Copyright and License Information

© 2023 The Author(s); Published by Hamadan University of Medical Sciences.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Please cite this article as follows: Kehinde LC, Mambetalina AS, Nurlan Oralbaevich B. Psychosocial-spiritual factors associated with wellbeing of older population in Africa. J Educ Community Health. 2023; 10(2):62-70. doi:10.34172/jech.2023.2289

Introduction

Aging is an inevitable developmental process that is accompanied by new opportunities and major changes that establish both the success and failure of the process. The increased number of old people in society according to the United Nations (UN) reflects a human success story of public health, improved standard of living, and medical achievements over early deaths that often curtail human life (1). However, the vulnerability that comes with this stage of life could be based on the new opportunities of being cared for, loved, valued, respected, and recognized which are also complemented by some changes such as a decrease in physical health as well as social-emotional and cognitive ability which are irreversible.

As part of the UN Sustainable Development Goals 2030 (SDG target 3), healthy lives and the promotion of the well-being of people of all ages are critical. Meanwhile, not many societies focus on the well-being of older people as much as they are expected, and they care for young people, which may truncate the full achievement of the fourth target of SDG target 3. In fact, some societies have negative attitudes towards older people due to the conventional belief that the older population is no longer useful to society (2). This stereotype may be further spurred by senescence, a developmental phenomenon characterized by the biological and psychosocial changes in the final stages of life. These changes have been categorized by the experts in the field of gerontology into three categories: bio-physiological (physical health and cognitive functioning), social (retirement, social, networks, connectedness, ties, support exchanges, and economy/finance status), and psychological (life satisfaction, adjustment, emotional stability, and well-being) (3,4). Thus, well-being refers to a state of optimal physical, mental, and social health and functioning (5). Despite these challenges, the plight of elderly people has not been the subject of concern in research, and they are becoming more depressed, dissatisfied with life, and lonelier thereby affecting their well-being (6).

In African society, such a high premium is placed on social respect for older people that regardless of their socioeconomic, political, or educational status, society provided them with respect and care (7). Moreover, the mutual obligations of members of both nuclear and extended families to care for the elderly are critical virtue to Africans. Unfortunately, these virtues are gradually eroding African society, causing abandonment and loneliness in older people, thus heightening emotional, physical, and social problems and declining well-being. The condition of the older population in Nigeria is worsening because of economic deprivation and poor access to health care services, aggravated by several months of unpaid retirement salaries and allowances (for those who were employed). Many are left with insufficient personal savings, ineffective or poorly managed pension schemes, haphazardly paid gratuities, and a lack of social incentives for senior citizens (8).

Unfortunately, the subjective well-being condition of older people in Nigeria, where no adequate provision is available to alleviate old age challenges, has not gained due attention. Although there is a provision in the Nigerian constitution of 1999 for the social welfare and healthcare service of the elderly, regrettably it has confronted a setback in its implementation. It is also disheartening seeing older people who have served the nation or their state in one capacity or another begging for arms on the Nigerian’s streets due to poorly managed pension schemes and haphazardly paid gratuity at both national and state levels. Most of their family members who should take care of them are also experiencing a similar situation such as several months of unpaid salaries and allowances (8). It is not irrelevant to say that poor conditions of the older people in Nigeria are a national embarrassment and have become a political campaign instrument that the politicians are now using each political year. Consequently, with lesser attention paid to the quality of subjective well-being of the older people, the generation gap may be widened between the younger and the older people, thereby eroding various indigenous cultures, morals, values, Ubuntu/ botho (dignity or humane), and traditions that defined African identities (9).

Apart from established fact that physical health diminishes with aging (10,11), subjective well-being also poses a similar threat to successful aging. However, difficulty to attain good physical health, cognitive and social functioning, as well as achieving economic independence may perhaps reduce the quality of well-being in older people. On the other hand, the well-being of elderly individuals could be proof of successful ageing. Thus, this study aimed to examine the psychosocial-spiritual factors associated with well-being in the older population in Africa with a focus on determining the contribution of all the psychosocial-spiritual factors when mediated by general health conditions.

Research evidence has shown that the poor condition of healthcare systems in Africa has continued to worsen the health challenges of the older population (10). The poor health conditions of the elderly in Africa include body pain, increased rates of HIV and AIDS, nervous disorders, musculoskeletal systems, and ocular diseases (10). For instance, in Southern Africa, it was found that chronic health-related problems common among the older population include HIV/AIDs, arthritis, dementia, and diabetes which are closely linked with obesity, reduced energy and physical activity, and high blood pressure (11-13). A study conducted in Botswana by the UN (14) revealed that muscle-skeletal pains, hypertension, dermatological problems, blindness, mental health, and cognitive impairment are the most common health challenges facing older people in the region. This outcome is not different from that of the study in Ghana that identified osteoarthritis, hypertension, and obesity as the most prevalent health burden of the older population (15). In the same manner, the health conditions of the older population in Nigeria are not in any way different from the rest of African countries as affirmed by Lloyd-Sherlock and Agrawal (16) who found that the majority of older people in Nigeria are suffering from poor multiple health conditions, including eyesight, hearing, kidney problems, Parkinson’s disease, urinary incontinence, cataract or glaucoma, and rheumatism or arthrosis. Evidently, the general health conditions of older people pose serious challenges to their well-being as well as their successful aging which has not been given adequate attention.

In addition to health conditions in an older population, psychosocial factors are vital to successful aging. Psychosocial-spiritual factors are the combination of psychological and social factors. In the present study, coping efficacy, self-esteem, and quality of life were considered psychological factors, while social integration, social network, and social support as social and religious spiritual factors (16,17) established that individual psychological resources such as ego-integrity, self-achievement, and self-esteem are important psychological factors for active successful aging. Other scholars have affirmed that older people’s well-being is faced with some psychological challenges ranging from lack of love and affection, emotional stress, feelings of disappointment or unhappiness, worries, lowered self-esteem, anxiety, stress, grief, and personality disorder to depression (18,19). Generally, the effects of these psychological problems are negative and devastating, posing serious threats to the well-being of the older population.

Specifically, coping efficacy was described by Waldrep (20) as the ability of an individual to meet the demands of traumatizing life experiences, as well as individual response to distressing experiences. It was also found that the awareness of potential coping efficacy in threatening situations affects motivation and cognitive efforts to regulate one’s behavior (21). Self-esteem, which is an individual’s opinion of self, plays a vital role in well-being. People with high levels of self-esteem feel valuable, worthy, and self-respected, while individuals with low self-esteem perceive themselves as valueless and worthless (22). Furthermore, success and life achievement are determined by the level of an individual’s self-esteem, and self-esteem is a vital key to life success (23). Hence, Qiu (22) asserted that healthy life, personal and social adjustment, as well as emotional well-being depend on the levels of one’s self-esteem to a large extent. Furthermore, quality of life as a psychological construct explains the perception of an individual’s position in life within the cultural context and value system in relation to goals, social relations, and expectations of the World Health Organization (WHO) (24). In a study by Morgan et al (25), it was indicated that good quality of life is an indicator of successful aging which enables individuals to adapt well in later life. In addition, Akinyemi et al (26) found that the adults living in suburban communities in Nigeria have a good quality of life. Another study by de Souza et al (27) revealed that quality of life positively influences the subjective well-being of senior citizens in Brazil. In a review study conducted by Attafuah et al (28) on the quality of life of older adults residing in African countries, the outcome of the study affirmed the low quality of life in the older population in African countries despite its significant role in the general well-being of older adults.

Socialization is pivotal to a healthy life and wellness. However, most older people are often experiencing social exclusion due to dissociation from the world of work. As noted by Adeleke et al (29), many older people are socially frustrated due to low social connections, loneliness, widowhood, lack of intimacy, and ageism. Similarly, Ayalew (30) alludes to the fact that social relationships throughout Africa are gradually being extinct because of the adoption of Western culture that does not value the practices of extended family, thereby reducing family and community support in old age. Hence, the intensified social difficulties of the older population due to restricted social contacts, poor social networking, lack of social support, social isolation, abandonment or neglect by family members, and occupational disengagement due to aging affect well-being in the elderly (31). Other studies in Nigeria linked the social vulnerability in an older population with the failure of various social security scheme implementation and sustainability and poor healthcare services (32,33).

Furthermore, previous studies have evidently demonstrated the relationship between a higher degree of social network and a lower risk of physiological distress in both early and later life (34). According to Zhang et al (35), social networks are correlated with the subjective well-being of elderly urban residents in China. Meanwhile, the decrease in social networks such as family, family tie structures, the lack of social programs, and disability-associated aging was found to be associated with the reduced quality of well-being of older persons in Nigeria. A study by Li et al (36) revealed that spousal support contributes to a decreased negative effect on the elderly, while support from friends increased the positive effect on the elderly in their study. In addition, Oluwagbemiga (37) discovered that social support such as companionship, emotional support, information access, and financial support positively and significantly influence the psychosocial well-being of the study’s participants. Recently, Tariq et al (38) reported that perceived social support from friends, family, and significant others prevents cognitive and physical health obstacles in old age.

Empirically, religiosity and spirituality are used interchangeably and have recently gained research attention in their predictive influence on health and general well-being. Religiosity has been described as a spiritual behavior of connecting individual who directs the behavior to God by praying, meditating, singing spiritual songs, and reading spiritual books (39). It reflects the ritualized practice or a mechanism that exerts protective effects on human life problems such as life-threatening health burdens (40). Additionally, Mitchell (41) stated that religiosity is a coping strategy for overcoming bereavement or the loss of loved ones. Another scholar remarked that religiosity is relevant to life situations or challenges and human existence when experiencing serious life challenges (42). Hence, religiosity involves an act of faith in divinity that gives strength to individuals who may be experiencing depressing or difficult situations. This act involves listening to sermons, singing, praying, and reading spiritual texts like the Holy Bible or Quran. Evidence has shown that older people tend to adopt religiosity as an important source of emotional support and coping with life stress because it creates a greater sense of hope, happiness, and coherence (42-44). Furthermore, religiosity has been found to be associated with enhancing global health and well-being (40,45). Unfortunately, no previous attempt has been identified to investigate the psychosocial-spiritual factors associated with the well-being of older people in Africa with the moderating effect of general health conditions. This study was then an attempt to bridge this gap. The authors aimed to examine the predictive power of psychosocial-spiritual factors on well-being in the African older population. The study also assessed the moderating influence of general health conditions in predicting well-being in the older population. It is hoped that the outcome of the study will open a novel avenue for further research, assessing the well-being of older people in Africa.

Hypotheses

The study was guided by two research hypotheses:

-

H1: There is the significant predictive contribution of psychosocial-spiritual factors such as integration, social network, social supports coping efficacy, self-esteem, religiosity, and quality of life to the well-being of the older population.

-

H1: There is a significant predictive association between psychosocial-spiritual factors and well-being as mediated by general health conditions of older people.

Methods and Materials

Design, Participants, and Procedure

This survey design was used to collect data from older people across five local municipals from September 21, 2019 to February 22, 2020 in Ibadan, Nigeria. This design was used due to the need for seeking robust views of the participant. The formula method of the infinite population was used to calculate the sample (> 10 000 subjects) n = z2 P*Q/E2. A total of 883 older people were obtained, exhibiting 3.3% for a 97% confidence interval in a margin of error. The participants were conveniently selected from three locations within the five local municipals, including pension offices, religious centers, and social milieus. The eligibility criteria were age 60 and above, completing an informed consent form, and the ability to read and write both in English and Yoruba languages.

Instruments

A self-structured questionnaire was adapted for data collection. The questionnaire comprises two sections of A and B. The first section focuses on the demographic information of the respondents which includes age, gender, and general health condition, while the second section consists of psychosocial-spiritual factors. Details of the instruments are as follows.

Well-being

The emotional well-being questionnaire (46) aimed to measure how happy and satisfied an individual is with life. The scale consists of 15 items (alpha = 0.89) scored on a 4-point Likert scale (4 = strongly agreed, 3 = agreed, 2 = disagreed, and 1 = strongly disagreed). An item of the questionnaire is: I am very excited about my life.

Coping Efficacy

The coping efficacy (47) measures the individual level of confidence to face and overcome challenges. Five items with the highest correlated value (alpha = 0.95) were adapted to be used in this study with an initial 10-point response format reduced to five (1 = not at all, 2 = at all, 3 = not sure, 4 = always, and 5 = very much). An item of the questionnaire is: I am confident in my ability to see positive aspects in all situations.

Self-esteem

The general self-esteem scale (48) which measures the global self-worth of the individual in terms of positive and negative sense of self was adopted. Only five items were extracted from the original 10 items because of the nature of the participants to avoid boredom. The scale (alpha = 0.92) is scored on a 4-point Likert with the strongest values of (4), (3), and (2), and the weakest value of (1). One item of the scale is: I have a lot to be proud of in my life.

Quality of Life

The WHO Quality of Life (24) with five domains was used to measure life quality, including physical health, psychology, social life, independent life, and the environment. The present study adopted one item from each domain. The scale (alpha = 0.93) is a 5-point Likert format (1 = very poor, 2 = poor, 3 = not sure, 4 = good, and 5 = very good). An example of the scale is: How often do you have negative feelings such as anxiety, blue mood, depression, and despair?

Social Integration

The social belongingness scale (49) was adopted for social integration with five items extracted from the initial eight items. The scale’s response format was reformatted from a 6-point to a 4-point type (4 = strongly agreed, 3 = agreed, 2 = disagreed, and 1 = strongly disagreed). The scale’s reliability coefficient was reported to be 0.98. One example of the scale is: I have a sense of disconnection from the world around me.

Social Networking

Social networking is the second part of the social connectedness scale (49). This component measures what constitutes a social network around individuals such as friends, family, religious groups, or society. The scale’s response format was also reformatted from a 6-point to a 4-point type (4 = strongly agreed, 3 = agreed, 2 = disagreed, and 1 = strongly disagreed). The scale’s reliability coefficient was reported to be 0.87. An example of the scale is: I bond with my family members more than anyone else.

Social Support

A multidimensional perceived social support scale (50) was adapted to measure social support. The scale aimed to evaluate the actual support received by an individual in terms of emotional, financial, mental, and social support. The original 12 items were reduced to five with a 7-point reduced to a 4-point type (4 = strongly agreed, 3 = agreed, 2 = disagreed, and 1 = strongly disagreed). The reliability coefficient value of 0.98 was obtained. An example of the questionnaire is: I have people I can discuss my deepest challenges.

Religiosity

The religiosity scale (51) was adapted to be used in this study. The target of the scale is to assess how individuals practice life and value the religious activities of their religious schools (e.g., Christianity, Islam, Hindus, and Jewish among others). Only five items were extracted from the 37 items with a 4-point response format (1 = I never do, 2 = sometimes, 3 = mostly, and 4 = I always do). The Cronbach alpha estimate of.94 was established. “My religious beliefs and activities that make me happy” is one of the examples of the scale. The questionnaire was completed as pen and paper self-administered.

Data Analysis

The descriptive statistics of frequency counts was performed to determine the demographic characteristics of the participants, while inferential statistic of the structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test the direct predictive power of the psychosocial-spiritual factors on well-being and to determine the predictive power of the factors on well-being when moderated by general health condition. Thus, each factor was regressed onto the moderating factor to estimate the direct effects between different measures. IBM AMOS 26.0 was used as a tool to perform the pattern of correlation. SEM is a family of statistical techniques that can be used to measure the directionality relationship of latent (exogenous or independent) and observed (endogenous and dependent) variables, generally including multiple regression and path analysis. The terms peculiar to SEM include model fit indices, chi-square statistic (χ2), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker Lewis index (TLI) also known as a non-normed fit index (NNFI), goodness-of-fit (GFI) index, adjusted goodness-of-fit (AGFI) index, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA).

Results

The demographic characteristics of the participants show that 54.8% (484) were females, while 399 (45.2%) were males with an average age of 68.04 ± 6.71 years. The general health conditions of the participants indicated that 500 (56.6%) persons appraised their general health condition to be good, 362 (40.9%) reported moderate health condition, and only 21 (2.4%) perceived their general health condition to be critical.

Hypothesis One

There is the significant predictive contribution of psychosocial-spiritual factors to the well-being of the participants.

Structural Equation Modelling

The result of Table 1 demonstrated that the Chi-square value of the proposed factors predicts well-being. The result revealed that chi-square is greater than 0.05. χ2 = 187.66 implies that the proposed factors are adequate and fell within the acceptable norm; hence, it is satisfactory enough to determine the well-being of the study participants. In addition, since the model fit is accepted, relative fix indices were further explored to determine the robustness of the proposed factors. GFI = 0.957 suggests a satisfactory fit, CFI = 0.909 is also highly satisfactory, and NFI = 0.907 suggests a 90% improvement in the fit model. Moreover, IFI = 0.911 is also within an accepted threshold, while TLI = 0.534 is less than the accepted value of > 0.90, which implies that the TLI is not accepted, but RMSEA indicates a perfect fit. In general, all psychosocial-spiritual factors (coping efficacy, self-esteem, quality of life, social integration, social network, social supports, and religiosity) are good predictors of well-being of the older people. According to the applied criteria of SEM, all measurement models in this study indicate satisfactory fit indices of the well-being of the participants.

Table 1.

Goodness-of-Fit Statistics for Psychosocial Factors on Emotional Well-being

|

Model

|

χ2

|

DF

|

GFI

|

CFI

|

NFI

|

IFI

|

TLI

|

RMSEA

|

| Well-being |

187.266 |

7 |

0.957 |

0.909 |

0.907 |

0.911 |

0.534 |

0.052 |

| Psychosocial-spiritual factors |

26.752 |

|

0.546 |

1.000 |

0.000 |

1.000 |

0.000 |

0.258 |

Note. χ2 = Chi-square; DF: Degrees of freedom; GFI: Goodness-of-fit index; CFI: Comparative fit index; NFI: Normed fit index; IFI: Incremental fit index; TLI: Tucker Lewis index; RMSEA: Root mean square error of approximation.

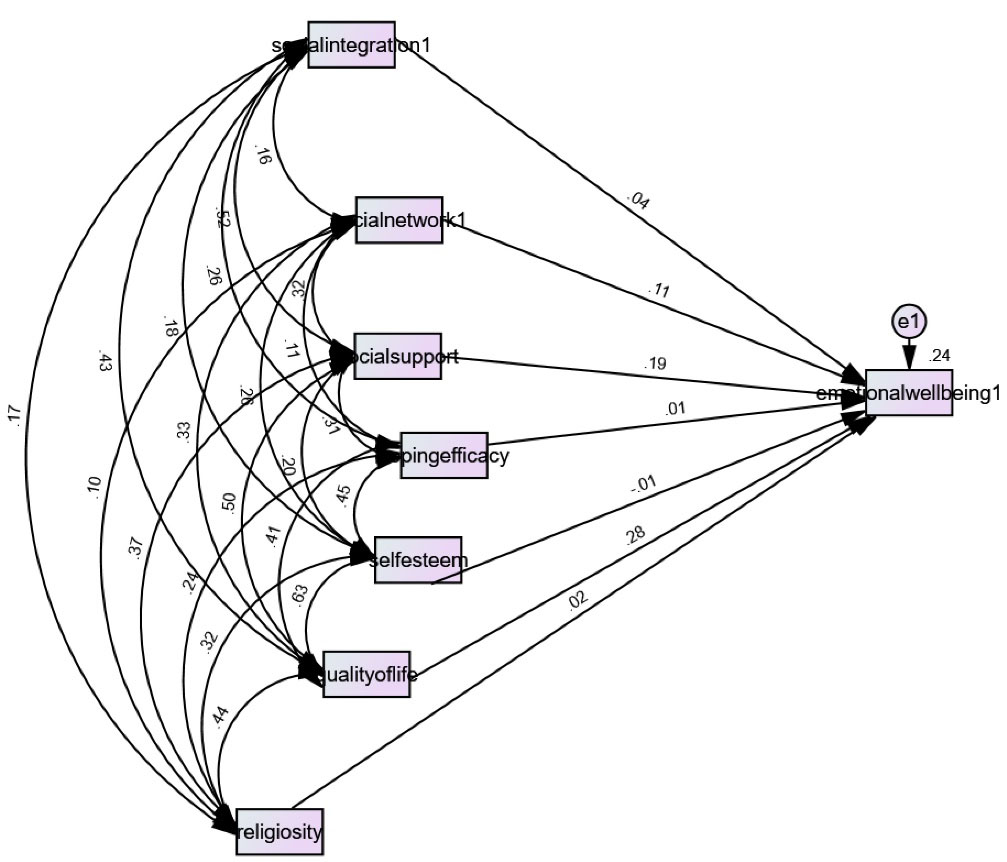

The path diagram and maximum likelihood estimation were performed to evaluate the SEM using AMOS 26.0 after the measurement model’s specification, and this is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Path Diagram for Psychosocial-spiritual Factors and Well-being of the Participants.

.

Path Diagram for Psychosocial-spiritual Factors and Well-being of the Participants.

Figure 1 indicates the significant prediction power of psychosocial-spiritual factors on the well-being of the participants. The path analysis displayed that quality of life accounted for the highest significant prediction of well-being (β: 0.28, P ≤ 0.001), followed by social support (β: 0.19, P ≤ 0.001) and social network (β: 0.11, P ≤ 0.001). However, social integration (β: 0.04, P > 0.001), religiosity (β: 0.02, P > 0.001), coping efficacy (β: 0.01, P > 0.001), and self-esteem (β: -0.01, P > 0.001) did not make any significant contribution to the prediction of well-being. This implies that the well-being of the older people who took part in this study was only determined by factors such as quality of life, social support, and social network, whereas social integration, coping efficacy, self-esteem, and religiosity did not statistically determine participants’ well-being.

Hypothesis Two

There is a significant predictive association between psychosocial-spiritual factors and emotional well-being mediated by general health conditions of older people.

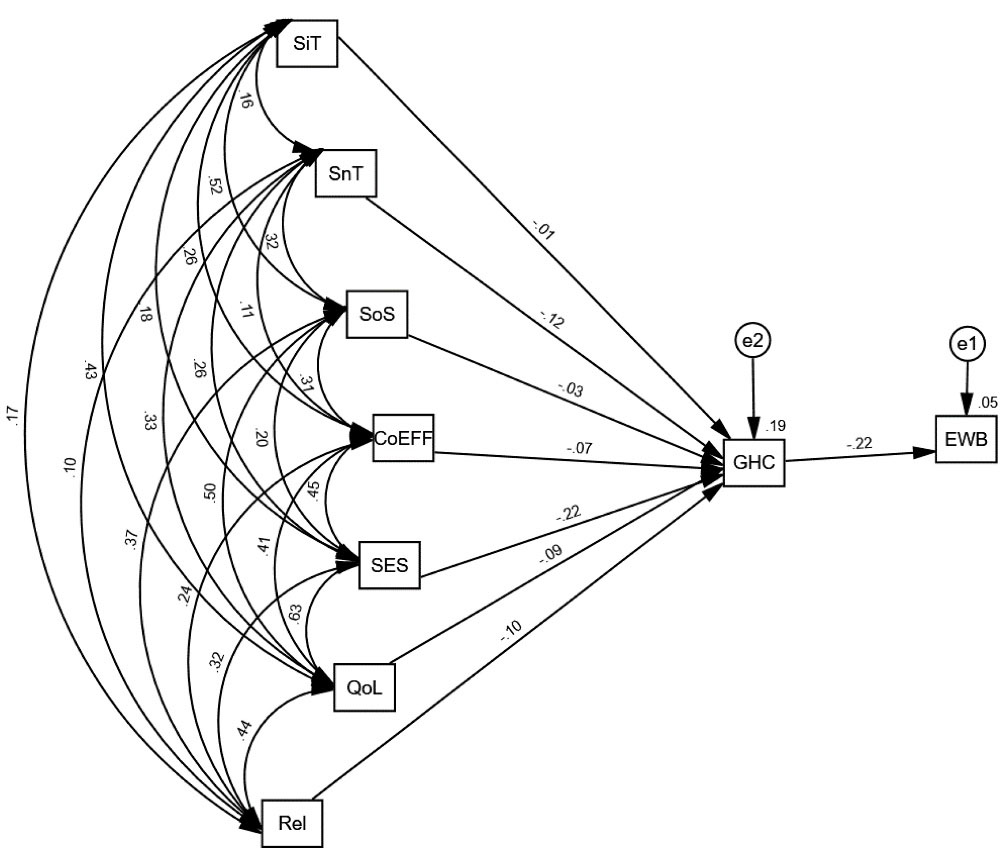

The path diagram in Figure 2 shows the significant predictive association between psychosocial-spiritual factors (coping efficacy, self-esteem, quality of life, social integration, social network, social supports, and religiosity) and emotional well-being moderated by general health conditions of the participants. The result demonstrated that the predictive association of all the factors was negatively significant (β: -0.22, P < 0.001) after being moderated by the general health condition, while the direct association between general health condition and well-being was positively significant (β: 0.19, P < 0.001). Further, all the psychosocial-spiritual factors were negatively associated with the general health condition, self-esteem (β: -0.22, P < 0.001), quality of life (β: -0.09, P > 0.001), coping efficacy (β: -0.07, P > 0.001), social integration (β: -0.01, P > 0.001), social network (β: -0.12, P > 0.001), social support (β: -0.03, P > 0.001), and religiosity (β: -0.01, P > 0.001). Thus, the inverse values suggest that there is no predictive association between the psychosocial-spiritual and well-being factors and the interference with the general health condition of the participants. This means that well-being of the older people depends on their general health condition.

Figure 2.

Path Diagram for Psychosocial-spiritual Factors of Well-being When Moderated by General Health Condition of the Participants.

.

Path Diagram for Psychosocial-spiritual Factors of Well-being When Moderated by General Health Condition of the Participants.

Discussion

This study assessed psychosocial-spiritual factors associated with the well-being of older people in Africa. The results suggest that more older people in Africa were in good and moderate health conditions. That is, despite the poor healthcare system in Nigeria, western region of Africa, the older population considered their general health to be good. The reason for this finding may be related to the public health and medical achievement success story of improved general health which has led to an increase in life expectancy (52). Furthermore, the average age of the participants was 68 years which is far above the life expectancy of 58 years (53), and also only healthy people can live longer. This outcome substantiates the finding of Audain et al (54) who revealed that older persons in Africa are at an increased risk of poor health despite poor healthcare facilities.

Moreover, the outcomes of this study indicated the predictive direct effect of all the psychosocial-spiritual factors (coping efficacy, self-esteem, quality of life, social integration, social network, social supports, and religiosity) to be significant on emotional well-being. The outcome of the first hypothesis revealed that three out of the seven factors (i.e., quality of life, social supports, and social network) made significant and direct positive contributions to emotional well-being in magnitude order, while the remaining four factors (i.e., social integrations, coping efficacy, self-esteem, and religion) did not have a direct contribution. Overall, the quality of life, social support, and social networks of older people who participated in the study have a direct contribution to emotional well-being. This finding is not unexpected since the quality of life of people is directly proportional to happiness and satisfaction. Social support in this study was not measured by the participant’s perception of it but rather by the actual or tangible support received from their social network. Hence, a social network for older people includes their relatives, friends, family members, and religious groups who were sources of help and assistance to them regularly.

This outcome supports the view that subjective well-being depends on the quality of life and that increasing the feeling of security that is social support influences emotional well-being (27,55). According to Rondón García and Ramírez Navarrro (56), quality of life is important in ensuring health and well-being at older age; additionally, quality of life among other factors exhibited the highest prediction of health wellness, psychological conditions such as life satisfaction, functional skills, and happiness. Equally, the study finding justifies the beneficial contribution of social support and social network to the emotional well-being of older people. This corroborates the study of Li et al (36) who reported that received material aids and emotional support ameliorate the negative effect on emotional well-being. Further, the social network which was described early in this study as the source of accessible or available help revealed significant contribution to well-being. This outcome validates several earlier studies (35,57-59) which found that primary social networks such as family members or relatives, friends, and acquaintances are associated with well-being and determine well-being by reducing negative affect such as loneliness in the older population.

Lastly, a novel finding of this study is that although quality of life, social support, and social network contribute to the well-being of the older population in Africa, the result of the moderating effect of general health conditions shows that no significant predictive contribution of coping efficacy, self-esteem, quality of life, social integration, social network, social supports, and religiosity to emotional well-being. This denotes that the general health condition of the elderly is a strong factor that can halt the influence of any other factors in predicting emotional well-being. In other words, this finding suggests that no matter the support, network, or perceived quality of life, as long as the general health condition is punctured, the consequences will be negative and affect emotions such as sadness, frustration, anxiety or worries, disgust, fatigue, and discomfort or unpleasant feelings. Although good health condition positively affects emotions in successful aging, poor health conditions of the elderly increase negative effects. Thus, positive emotional effects are sensitive to the general health condition of the elderly. This means that the positive effect of the emotional well-being of older people is susceptible to their general health conditions. Hence, this provides motivation for improving the healthcare system and health conditions in Africa.

This finding is consistent with studies of Charles (60) and Ferguson & Goodwin (61) that old age stressors are related to health vulnerabilities and functional limitations and weaken positive effects of emotional well-being possibly due to limited sensitization about health problems; that is, general health condition signifies threat to successful aging. It was reported that health sensitivity decreases with age and affects general well-being (62). The current finding is also consistent with the study of Won et al (63), showing that the influence of physical activity increases subjective well-being after being mediated by gender and perceived social support. In line with the existing evidence (64), mental health mediated the link between resilience and physical quality of life, while resilience partially mediated the relationship between loneliness and mental quality of life. Thus, general health conditions mediate the predictive effect of psychosocial-spiritual on well-being in older people. This is an advancement over previous empirical studies (38,44,56) on the association between psychosocial-spiritual and well-being in the older population in Africa.

This study is not without some shortcomings. First, it relied on self-report data, which may cause a bias. It also employed a quantitative method, thus further research should use the mixed-method approach which would allow the participants to express their feelings. In addition, causal factors of successful aging are not exhaustive, and only seven factors were considered in the study. Despite these limitations, the strength of the study lies in its large sample size with no missing data. Hence, the outcomes of the current study are robust and can be generalized in the field of older population studies, humanity, and gerontology for future research and practices.

Conclusion

This study concluded that among other factors, general health condition, quality of life, social support, and social network demonstrate a significant association with the subjective well-being of older people in Africa. Quality of life, social support, and social network directly predicted subjective well-being, and when general health condition was introduced to mediate the association, all the psychosocial-spiritual factors were inversely associated with well-being. These findings suggest that the well-being of the older population depends on their perceived general health conditions. Based on these findings, it is recommended that adequate attention should be given to the well-being of the older population for the realization of the UN SDG target 3 which focuses on ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all at all ages as this reflects a commitment to its achievement. Government, agencies, philanthropists, non-governmental organizations, and the general public should be concerned with the well-being of older people for cultural values and heritage sustainability. The presence of older people is vital to preserving cultural heritage. Effective implementation and adequate funding of social welfare policy for the elderly as well as healthcare facilities are suggested to promote the well-being of all individuals. Considering these changes will help them to still contribute meaningfully to the growth and development of African society, recognizing that older people are huge assets to their families, society, and upcoming generation. Hence, they help bridge the gap between the present and upcoming generations and more importantly play a mentorship role in society.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contribution of all the older people who volunteered to participate in this study by responding to the questionnaire distributed to them are returned.

Authors’ Contribution

Conceptualization: Lawrence Clement Kehinde.

Data curation: Lawrence Clement Kehinde.

Formal analysis: Aliya Saktaganovna Mambetalina.

Investigation: Lawrence Clement. Kehinde.

Methodology: Baigabylov Nurlan Oralbaevich.

Project administration: Lawrence Clement Kehinde.

Resources: Baigabylov Nurlan Oralbaevich.

Software: Lawrence Clement. Kehinde.

Supervision: Aliya Saktaganovna Mambetalina.

Validation: Baigabylov Nurlan Oralbaevich.

Visualization: Aliya Saktaganovna Mambetalina.

Writing–original draft: Baigabylov Nurlan Oralbaevich.

Writing–review & editing: Aliya Saktaganovna Mambetalina.

Competing Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this work is not available publicly but could be provided by the author on reasonable request.

Ethical Approval

Ethical clearance was granted by both the Social Science and Humanities Research Ethics Committee (SSHREC) with Ethical ID number UI/SSHREC/2019/129, and the Ministry of Health. The Informed Consent Form was presented before administration of the questionnaires. Older people who consented were assured that the information gathered would be used for research purposes only. The participants were assured of the confidentiality of the information provided. They were further informed that there were no right or wrong answers as their responses were expressions of their perceived psychosocial-spiritual indicators of their well-being.

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Health Inequalities in Old Age. 2018. https://www.un.org/development/desa/ageing/wp-content/uploads/sites/24/2018/04/Health-Inequalities-in-Old-Age.pdf. Accessed August 2022.

- Gonzalez RE. Risk Factors Associated with Depression and Anxiety in Older Adults of Mexican Origin [dissertation]. Walden University; 2015.

- Aw S, Koh GCH, Tan CS, Wong ML, Vrijhoef HJM, Harding SC. Theory and design of the Community for Successful Ageing (ComSA) program in Singapore: connecting BioPsychoSocial health and quality of life experiences of older adults. BMC Geriatr 2019; 19(1):254. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1277-x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Grover S. Successful aging. J Geriatr Ment Health 2016; 3(2):87-90. doi: 10.4103/2348-9995.195595 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Definition of Health. 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/constitution.

- Allen J. Older People and Wellbeing. London: Institute for Public Policy Research; 2008. https://www.ippr.org/files/images/media/files/publication/2011/05/older_people_and_wellbeing_1651.pdf.

- Oluwabamide AJ, Eghafona KA. Addressing the challenges of ageing in Africa. Anthropologist 2012; 14(1):61-6. doi: 10.1080/09720073.2012.11891221 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sanuade OA, Ibitoye OG, Adebowale AS, Ayeni O. Psychological well-being of the elderly in Nigeria. Niger J Sociol Anthropol 2014; 12(1):74-85. doi: 10.36108/njsa/4102/12(0150) [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Makhonza LO, Lawrence KC, Nkoane MM. Polygonal ubuntu/botho as a superlative value to embrace orphans and vulnerable children in schools. Gend Behav 2019; 17(3):13522-30. doi: 10.10520/EJC-19745b196c [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jogerst GJ, Wilbur JK. Care of the elderly. In: Rakel RE, ed. Textbook of Family Practice. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Company; 2007. p. 65-105.

- Tappen RM, Newman D, Gropper SS, Horne C, Vieira ER. Factors associated with physical activity in a diverse older population. Geriatrics (Basel) 2022; 7(5):111. doi: 10.3390/geriatrics7050111 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Maniragaba F, Nzabona A, Asiimwe JB, Bizimungu E, Mushomi J, Ntozi J. Factors associated with older persons’ physical health in rural Uganda. PLoS One 2019; 14(1):e0209262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209262 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Douglass R. The aging of Africa: challenges to African development. Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev 2015; 16(1):1-15. [ Google Scholar]

- Kasiram M, Hölscher D. Understanding the challenges and opportunities encountered by the elderly in urban KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. S Afr Fam Pract 2015; 57(6):380-5. doi: 10.1080/20786190.2015.1078154 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division 2015. Directory of Research on Ageing in Africa: 2004-2015 (ST/ESA/SER.A/391). 2015. Available at: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/Dir_Research_Ageing_Africa_%202004-2015.pdf. Accessed September 2022.

- Lloyd-Sherlock P, Agrawal S. Pensions and the health of older people in South Africa: is there an effect?. J Dev Stud 2014; 50(11):1570-86. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2014.936399 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Khanam MA, Streatfield PK, Kabir ZN, Qiu C, Cornelius C, Wahlin Å. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity among elderly people in rural Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. J Health Popul Nutr 2011; 29(4):406-14. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v29i4.8458 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kim SK. A randomized, controlled study of the effects of art therapy on older Korean-Americans’ healthy aging. Arts Psychother 2013; 40(1):158-64. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2012.11.002 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Orth U, Robins RW, Widaman KF. Life-span development of self-esteem and its effects on important life outcomes. J Pers Soc Psychol 2012; 102(6):1271-88. doi: 10.1037/a0025558 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Waldrep EE. Coping Self-Efficacy as a Mechanism of Resilience Following Traumatic Injury: A Linear Growth Model [dissertation]. Kent State University; 2015.

- Rautenbach E. Perceived Stress, Coping Self-Efficacy and Adaptive Coping Strategies of South African Teachers [dissertation]. Vanderbijlpark: North-West University (NWU); 2019.

- Qiu X. Self-Esteem, Motivation, and Self-Enhancement Presentation on WeChat [dissertation]. University of South Florida; 2018.

- Hill E. The Relationship Between Self-Esteem, Subjective Happiness and Overall Life Satisfaction [dissertation]. Dublin: National College of Ireland; 2015.

- The WHOQOL Group. The development of the World Health Organization quality of life assessment instrument (the WHOQOL). In: Orley J, Kuyken W, eds. Quality of Life Assessment: International Perspectives. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 1994. p. 41-57. 10.1007/978-3-642-79123-9_4.

- Morgan UM, Etukumana EA, Abasiubong F. Sociodemographic factors affecting the quality of life of elderly persons attending the general outpatient clinics of a tertiary hospital, South-South Nigeria. Niger Med J 2017; 58(4):138-42. doi: 10.4103/nmj.NMJ_124_17 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Akinyemi OO, Owoaje ET, Popoola OA, Ilesanmi OS. Quality of life and associated factors among adults in a community in South West Nigeria. Ann Ib Postgrad Med 2012; 10(2):34-9. [ Google Scholar]

- de Souza LN, de Carvalho PH, Ferreira ME. Quality of life and subjective well-being of physically active elderly people: a systematic review. J Phys Educ Sport 2018; 18(3):1615-23. doi: 10.7752/jpes.2018.03237 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Attafuah PY, Everink IH, Halfens RJ, Lohrmann C, Abuosi A, Schols JM. Instruments for assessing quality of life among older adults in African countries: a scoping review. Res Sq [Preprint]. 2019. Available from: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-6095/v1.

- Adeleke RO, Adebowale TO, Oyinlola O. Profile of elderly patients presented with psychosocial problems in Ibadan. MOJ Gerontol Ger 2017; 1(1):26-36. doi: 10.15406/mojgg.2017.01.00006 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ayalew E. The Social and Economic Conditions of the Older People in Addis Ababa: The Case of a Charity Association for the Destitute and Abandoned People [dissertation]. Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University; 2019.

- Paskaleva D, Tufkova S. Social and medical problems of the elderly. J Gerontol Geriatr Res 2017; 6(3):1-5. doi: 10.4172/2167-7182.1000431 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Daramola OE, Awunor NS, Akande TM. The challenges of retirees and older persons in Nigeria; a need for close attention and urgent action. Int J Trop Dis Health 2019; 34(4):1-8. doi: 10.9734/IJTDH/2018/v34i43009 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yakubu A. Old age vulnerability and formal social protection in Nigeria: the need for renewed focus on prospects of informal social protection. Int J Appl Res Soc Sci 2019; 1(4):138-58. doi: 10.51594/ijarss.v1i4.39 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yang YC, Boen C, Gerken K, Li T, Schorpp K, Harris KM. Social relationships and physiological determinants of longevity across the human life span. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016; 113(3):578-83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511085112 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Zhang J, Zhao N, Yang Y. Social network size and subjective well-being: the mediating role of future time perspective among community-dwelling retirees. Front Psychol 2019; 10:2590. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02590 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Li H, Ji Y, Chen T. The roles of different sources of social support on emotional well-being among Chinese elderly. PLoS One 2014; 9(3):e90051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090051 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Oluwagbemiga O. Effect of social support systems on the psychosocial well-being of the elderly in old people s homes in Ibadan. J Gerontol Geriatr Res 2016; 5(5):1-9. doi: 10.4172/2167-7182.1000343 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Tariq A, Beihai T, Abbas N, Ali S, Yao W, Imran M. Role of perceived social support on the association between physical disability and symptoms of depression in senior citizens of Pakistan. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17(5):1485. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051485 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Aukst-Margetić B, Margetić B. Religiosity and health outcomes: review of literature. Coll Antropol 2005; 29(1):365-71. [ Google Scholar]

- Zimmer Z, Jagger C, Chiu CT, Ofstedal MB, Rojo F, Saito Y. Spirituality, religiosity, aging and health in global perspective: a review. SSM Popul Health 2016; 2:373-81. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.04.009 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mitchell C. Effect of Religion on Domestic Violence Perpetration Among American Adults [thesis]. University of Missouri–St. Louis (UMSL); 2019. https://irl.umsl.edu/thesis/348.

- Zenevicz L, Moriguchi Y, Madureira VS. [The religiosity in the process of living getting old]. Rev Esc Enferm USP 2013; 47(2):433-9. doi: 10.1590/s0080-62342013000200023.[Portuguese] [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Amadi KU, Uwakwe R, Ndukuba AC, Odinka PC, Igwe MN, Obayi NK. Relationship between religiosity, religious coping and socio-demographic variables among out-patients with depression or diabetes mellitus in Enugu, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci 2016; 16(2):497-506. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v16i2.18 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ebimgbo S, Agwu P, Okoye U. Spirituality and religion in social work. In: Social Work in Nigeria: Book of Readings. University of Nigeria Press Ltd; 2017. p. 93-103.

- Kim-Prieto C, Miller L. Intersection of religion and subjective well-being. In: Diener E, Oishi S, Tay L, eds. Handbook of Well-Being. Salt Lake City, UT: DEF Publishers; 2018.

- Şimşek ÖF. An intentional model of emotional well-being: the development and initial validation of a measure of subjective well-being. J Happiness Stud 2011; 12(3):421-42. doi: 10.1007/s10902-010-9203-0 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Neilands TB, Chambers DB, Taylor JM, Folkman S. A validity and reliability study of the coping self-efficacy scale. Br J Health Psychol 2006; 11(Pt 3):421-37. doi: 10.1348/135910705x53155 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg R. Strengthening Social Networks of Youth Aging Out of Foster Care: Promoting Positive Adult Outcomes [thesis]. Virginia Commonwealth University; 2018.

- Lee RM, Robbins SB. Measuring belongingness: the social connectedness and the social assurance scales. J Couns Psychol 1995; 42(2):232-41. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.42.2.232 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess 1988; 52(1):30-41. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hernandez BC. The Religiosity and Spirituality Scale for Youth: Development and Initial Validation [thesis]. Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College; 2011. 10.31390/gradschool_dissertations.2206.

- Lawanson OI, Umar DI. The life expectancy-economic growth nexus in Nigeria: the role of poverty reduction. SN Bus Econ 2021; 1(10):127. doi: 10.1007/s43546-021-00119-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Life Expectancy at Birth, Total (Years)-Nigeria. World Bank; 2022.

- Audain K, Carr M, Dikmen D, Zotor F, Ellahi B. Exploring the health status of older persons in sub-Saharan Africa. Proc Nutr Soc 2017; 76(4):574-9. doi: 10.1017/s0029665117000398 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Iciaszczyk N. Social Connectedness, Social Support and the Health of Older Adults: A Comparison of Immigrant and Native-Born Canadians [dissertation]. Canada: The University of Western Ontario; 2016.

- Rondón García LM, Ramírez Navarrro JM. The impact of quality of life on the health of older people from a multidimensional perspective. J Aging Res 2018; 2018:4086294. doi: 10.1155/2018/4086294 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Akosile CO, Mgbeojedo UG, Maruf FA, Okoye EC, Umeonwuka IC, Ogunniyi A. Depression, functional disability and quality of life among Nigerian older adults: prevalences and relationships. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2018; 74:39-43. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2017.08.011 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ojagbemi A, Gureje O. Typology of social network structures and late-life depression in low- and middle-income countries. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 2019; 15:134-42. doi: 10.2174/1745017901915010134 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ojembe BU, Ebe Kalu M. Describing reasons for loneliness among older people in Nigeria. J Gerontol Soc Work 2018; 61(6):640-58. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2018.1487495 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Charles ST. Strength and vulnerability integration: a model of emotional well-being across adulthood. Psychol Bull 2010; 136(6):1068-91. doi: 10.1037/a0021232 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SJ, Goodwin AD. Optimism and well-being in older adults: the mediating role of social support and perceived control. Int J Aging Hum Dev 2010; 71(1):43-68. doi: 10.2190/AG.71.1.c [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Schöllgen I, Morack J, Infurna FJ, Ram N, Gerstorf D. Health sensitivity: age differences in the within-person coupling of individuals’ physical health and well-being. Dev Psychol 2016; 52(11):1944-53. doi: 10.1037/dev0000171 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Won D, Bae JS, Byun H, Seo KB. Enhancing subjective well-being through physical activity for the elderly in Korea: a meta-analysis approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 17(1):262. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17010262 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gerino E, Rollè L, Sechi C, Brustia P. Loneliness, resilience, mental health, and quality of life in old age: a structural equation model. Front Psychol 2017; 8:2003. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02003 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]