J Educ Community Health. 11(3):133-143.

doi: 10.34172/jech.2837

Original Article

Exploring Facilitators of Family-Based Sexual Health Education in Northern Nigeria: A Qualitative Study

Abubakar Salisu 1  , Mahmood Saeedy Rezvani 2, *

, Mahmood Saeedy Rezvani 2, *  , Hosein Kareshki 1

, Hosein Kareshki 1  , Seyyed Mohsen Asgharinekah 1

, Seyyed Mohsen Asgharinekah 1  , Abdullahi Aliyu Dada 3

, Abdullahi Aliyu Dada 3

Author information:

1Department of Counselling and Educational Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran

2Department of Curriculum Studies and Instruction, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran

3Department of Educational Foundations and Curriculum, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria

Abstract

Background: Family-based sexual health education is critical as it plays a crucial role in promoting well-being by fostering healthy attitudes and behaviors toward sexuality. This study investigated educators’ perspectives on the factors that facilitate the successful implementation of family-based sexual health education in Northern Nigeria.

Methods: This qualitative study utilized a phenomenological research approach. Data were collected through open-ended interviews with faculty members from universities and health practitioners across five states in northern Nigeria. Participants were purposefully selected to take part in the study interviews based on their practical and research experience in the subject matter. Data were analyzed using Colaizzi’s method.

Results: Interviews with 18 educators revealed 17 subthemes, which were classified into three main themes: caregivers’ competence, adequacy of external resources and support, and culturally proportionate content.

Conclusion: The study provides valuable insights into the conditions necessary to promote sexual health education and establish a supportive environment for open discussions and effective interventions within families in Northern Nigeria.

Keywords: Educators’ perspectives, Facilitating factors, Family-based sexuality education, Northern Nigeria, Sexual health education

Copyright and License Information

© 2024 The Author(s); Published by Hamadan University of Medical Sciences.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Please cite this article as follows: Salisu A, Saeedy Rezvani M, Kareshki H, Asgharinekah SM, Dada AA. Exploring facilitators of family-based sexual health education in Northern Nigeria: a qualitative study. J Educ Community Health. 2024; 11(3):133-143. doi:10.34172/jech.2837

Introduction

The prevalence of sexual offenses and risky sexual behaviors among teenagers is rising in many countries globally due to restrictions on sex education programs (1). These restrictions have resulted in reproductive consequences, including early engagement in sexual activity, unwanted pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and abortions among adolescents (2). The lack of essential guidance for young children and adolescents has been identified as a significant factor contributing to such outcomes among youth in Nigeria (3-5). To address the challenges posed by this educational inadequacy, it is necessary to implement sex education within the family system, which serves as the primary educating agent for establishing a foundation of health and well-being before formal education begins (6).

A literature review on the factors influencing the implementation of sexual health education programs in family settings has revealed several pivotal factors that can significantly improve the overall implementation process (7). For example, Goldman (8) reported the significance of genetic factors, social influences, educational policies, parents’ level of sexual health literacy, and their ability to address the academic needs within the family as key determinants of effective sexual health education. Other studies highlighted the influence of parenting style and attachment on the outcomes of sexual health education (9). However, factors like misconceptions about sexual health education, cultural norms, and societal barriers continue to hinder the implementation of family-based sexuality education in Nigeria (10). A comparison between the northern and southern regions of the country reveals that the implementation of sexuality education is less effective in northern Nigeria due to cultural norms, religiosity, and economic situations (11,12). Parents often feel unmotivated and uncomfortable discussing sexual topics with their children (13), which can hinder children’s access to the necessary educational content and the development of sex-related competencies (14).

Sexuality education is a lifelong process through which individuals can acquire the knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and skills that contribute to their sexual and reproductive health. This can enhance the overall quality of life for young children and adolescents (15,16). Family-based interventions, including parent-child communications on topics such as puberty, STIs, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention, sexual relationships, and nutrition (17) can play a vital role in preventing sexual violence and fostering healthy sexual identity development (18,19). Furthermore, these interventions can effectively reduce risky sexual behaviors (20), promote informed and healthy decision-making (21), address cyber-poly victimization (22), and meet the sexual health education needs of children with clinical conditions (23).

Several studies suggest that parent-focused sex education programs can be enhanced by incorporating scientifically validated theories (15). However, the most commonly used approach relies heavily on social learning, which focuses on providing information and encouraging parent-child communication (15). Nevertheless, an intervention that solely focuses on imparting information and raising awareness may be insufficient (24). This limitation could explain why sex education has had a limited impact on children in many countries. Pop and Rusu identified several key components essential for effective sexual health education, including easy access to resources, comprehensive program development, appropriate timing, personalized service delivery, and addressing known risk factors (7). However, educational programs that meet these requirements and fully embody the ideals of sexual health education are lacking at both school and family levels. In Nigeria, no specific curriculum exists that focuses on sexual health education in family settings or meets the cultural needs of the region, despite other studies emphasizing the importance of cultural sensitivity as a foundation for effective sexual health education in the country (11,25). However, this sensitivity practiced within family settings remains unclear. Some scholars advocate for a conciliatory approach that integrates scientific findings with cultural norms, suggesting that merging cultural values with scientific findings can enhance the effectiveness of implementation (13), while others argue for a science-based approach, stressing the need for public education on sexual health (17). To determine a more suitable and effective approach, it is necessary to find an ideal approach that addresses sexual health issues within the cultural context of the region.

This study, therefore, aimed to explore educators’ perspectives on how family-oriented sexual health education is facilitated in Northern Nigeria. The study also sought to reveal the perspectives and experiences of professionals regarding sexual health education in the cultural context of Northern Nigeria and how it is implemented in family settings.

The specific goals of the study are:

-

To examine the attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions of education professionals toward sexuality education in Northern Nigeria.

-

To explore the culturally relevant facilitating factors of sexual health education and the expected outcomes in northern Nigeria.

By addressing these objectives, this study aimed to contribute to the existing literature on sexual health education in Nigeria and provide recommendations for policymakers, educators, and other stakeholders involved in promoting sexual health education.

Materials and Methods

Research Approach and Design

This qualitative study applied a phenomenological approach to identify how educators perceive the process of sexuality education within the family context in Northern Nigeria. The phenomenological method was used to describe and interpret the common experiences of individuals by determining the meanings they ascribe to those experiences (26,27)

Participants and Setting

The study involved 18 purposefully recruited participants, consisting of 7 health practitioners, (3 public health practitioners and 4 psychologists) and 11 non-health professionals (4 educational experts, 4 sociologists, and 3 religious scholars). All participants were recruited from the Faculties of Education, Psychology, Social Sciences, and other health centers across five states in northern Nigeria. The participants’ ages ranged from 34 to 60 years, with a mean age of 43.11. Inclusion criteria required participants to be married, have a child, and possess practical or research expertise in sexuality education. To protect the participants’ identities, their names were replaced with codes indicating their profession or field of study such as PS-01 for Psychologist 1, HO for Health Officer, SO for Sociologist, ED for Educationist, and RS for Religious Scholar. The demographic information of the participants is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ Demographic Information

|

#

|

Gender

|

Age

|

Education

|

Academic/Occupational Status

|

State of Origin

|

| 1 |

Male |

40 |

M.A in Health Education |

Public Health Officer |

Katsina State |

| 2 |

Male |

43 |

Ph.D. in Sociology of Education |

Assistant Lecturer |

Sokoto State |

| 3 |

Female |

41 |

Ph.D. in Sociology |

Assistant Lecturer |

Kebbi State |

| 4 |

Male |

55 |

Ph.D. in Sociology |

Professor |

Sokoto State |

| 5 |

Male |

34 |

M.A in Health Education |

Public Health Officer |

Katsina State |

| 6 |

Male |

38 |

M.A in Psychology |

School Psychologist |

Katsina State |

| 7 |

Male |

47 |

Ph.D. in Adult Education |

Associate Professor |

Kano State |

| 8 |

Male |

45 |

M.A in Religious (Islamic) Studies |

Graduate Assistant (Instructor) |

Katsina State |

| 9 |

Male |

40 |

M.A in Adult Education |

Graduate Assistant (Instructor) |

Kano State |

| 10 |

Male |

41 |

M.A in Psychology |

School Psychologist |

Katsina State |

| 11 |

Male |

35 |

M.A. in Education (Instructional Technology) |

Graduate Assistant (Instructor) |

Kano State |

| 12 |

Male |

51 |

Ph.D. in Instructional Technology and Curriculum Development |

Associate Professor |

Kaduna State |

| 13 |

Male |

60 |

Ph.D. in Religious Studies |

Professor |

Kaduna State |

| 14 |

Female |

39 |

M.A in Religious Studies |

Graduate Assistant (Instructor) |

Katsina State |

| 15 |

Female |

40 |

Ph.D. in Social Psychology |

Assistant Lecturer |

Kaduna State |

| 16 |

Female |

38 |

Ph.D. in Sociology of Education |

Graduate Assistant (Instructor) |

Kaduna State |

| 17 |

Male |

49 |

Ph.D. in Health Policy and Management |

Healthcare Management and Administration Officer |

Kaduna State |

| 18 |

Male |

40 |

Ph.D. in Educational Psychology |

Assistant Lecturer |

Kaduna State |

Note. M.A: Master of Arts; Ph. D: Doctor of Philosophy.

Data Collection and Procedure

All participants were involved in a semi-structured interview that focused on their experiences with family-oriented (home-based or parent-focused) sexuality education in northern Nigeria. They also discussed their interpretations of sexual health education and how it is facilitated in the region. The interviews lasted between 38 and 79 minutes. Before the interviews, the researchers contacted each participant individually and provided them with a participant package containing a pen, a research introduction letter, an information sheet, and an informed consent form. The participants were asked the following questions: “What have you experienced in the process of providing sexuality education in northern Nigeria? What challenges have you faced in the process of implementing sexuality education? What processes are needed to improve the provision of sexuality education in northern Nigeria?”

Data Analysis

The researchers employed Colaizzi’s method to analyze the obtained data. Initially, the interviewer collected the participants’ descriptions and reviewed them to grasp their meanings. The researchers then extracted the most important sentences and conceptualized the key themes. After categorizing the concepts and topics, a comprehensive description of the examined issue was provided. MAXQDA 20 software was used to facilitate data management and analysis. To ensure data validation, the researchers followed four guidelines introduced by Lincoln and Guba.

Data Rigour

To ensure the credibility and dependability of the research findings, the researchers approached the data with an open and neutral mindset. In addition to member checking, an external observer with expertise in qualitative research reviewed and validated the data coding process. The researchers used a standardized instrument for data collection and maintained clear records of the participants’ responses, including transcripts, notes, and audio recordings.

Results

Analysis of data from 18 interviews unveiled three significant themes that represent the factors facilitating family-oriented sexuality education in northern Nigeria, as perceived by the participating educators. These themes are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Identified Themes and Sub-themes Related to the Research Findings

|

Themes

|

Subthemes

|

| Caregivers’ competence |

Communication skills |

| Environmental management and monitoring |

| Modeling skills |

| Media-based literacy |

| Psychological attributes |

| Adequacy of external resources and support |

Stronger involvement of the legal system |

| Advocating for a communal approach |

| Professional intervention |

| Home-school cooperation |

| Utilization of religious opportunities |

| Culturally proportionate content |

Hygienic procedure and disease prevention |

| Sexual abuse prevention |

| Gender-related orientation |

| Puberty and reproductive health education |

| Family rules and boundaries |

| Abstinence and self-control |

| Decision-making skills |

Theme 1. Caregivers’ Competence

This subtheme encompasses participants’ views on the essential attributes and skills required for sexual health education within the family setting. These skills and attributes enable parents to utilize the educational opportunities, provide the necessary information, model desired behaviors, and address critical situations related to sexual health and well-being (Table 3).

Table 3.

Identified Codes and Sub-themes Related to the Main Theme of “Caregivers’ Competence”

|

Subthemes

|

Codes

|

| Communication skills |

Making comfort and building rapport in communication |

| Ability to provide sexual health information |

| Responding to children’s sexual questions appropriately |

| Active engagement to promote responsible decisions |

| Environmental management and monitoring |

Management of peer relationships |

| Use of social boundaries and restrictions |

| Monitoring of school activities |

| Play-time monitoring |

| Modeling skills |

Demonstration of desired positive behaviors |

| Expression of positive sexual attitudes |

| Using stories and tales to promote sexual health awareness |

| Media-based literacy |

Ability to give proper instruction about the usage of media |

| Ability to manage media activities |

| Psychological attributes |

Emotion regulation |

| Persistence and tolerance |

| Supportive parenting approach |

Communication Skills

Effective communication is essential for achieving the goals of sexuality education. This requires building a strong rapport between parents and children as an essential condition for imparting sexual health knowledge. Such rapport fosters a sense of comfort, which is crucial for open communication and seeking help in various situations. As stated by a health educator, “Parents should maintain a close relationship with their children and foster a sense of comfort, as without it, some children may not feel at ease discussing such matters.” (HO-02)

Another facet of parent-child communication pertains to the ability to respond to children’s inquiries about sexuality in a suitable manner. One respondent noted that addressing children’s questions can be a challenging task:“Children aged three to seven often pose numerous questions. Occasionally, when faced with inquiries to which I cannot immediately respond, I choose to remain silent. In other instances, I may provide them with clever or puzzling responses.” (ED-03)

This statement highlights the importance of equipping parents with guidelines on how to appropriately address children’s inquiries. Other participants stressed the need to tailor responses to children’s developmental stage: “They pose questions on various topics such as childbirth, paternity, and their own birth. Sex education here involves offering appropriate guidance in a manner suitable for their age.” (SO-03)

Through active and effective communication regarding sexual health, parents can guide their children in making responsible decisions. One participant underscored the importance of this by stating: “At times, it is necessary to raise awareness in a manner that prevents them from putting themselves in harm’s way, for instance, by explaining that certain actions could lead to undesirable consequences. These awareness efforts can deter risky behaviors.” (ED-03).

Monitoring and Environmental Management

Participants highlighted the significance of actively monitoring children’s behavior to detect any changes and respond accordingly. Furthermore, they underscored the need to stay vigilant about their children’s surroundings, friendships, and interactions at school. One parent explained: “I will dedicate a day to staying at home and observing their behavior a responsible adult has to stay informed about their actions. If I observe any slight changes in the children’s behavior, I will inquire.” (ED-01)

In addition to monitoring procedures, participants discussed strategies for managing thev environment and preventing inappropriate behavior such as establishing rules, boundaries, and limitations: “When a girl reaches puberty, she should be instructed about what is permissible and what is not. For instance, she should avoid mixing with boys, and parents should ensure they are separated from boys during sleep.”(SO-01)

The limitations were as a way to encourage abstaining from sexual activity: “When restrictive measures are enforced in schools, hospitals, and other public settings where relationship rules are enforced, individuals tend to suppress their sexual desires due to the lack of access to such relationships.” (HO-01)

Modeling Skills

The educators stressed the significance of parents acting as positive role models for their children as children frequently learn by imitating their parents’ actions. One participant noted that parents can effectively educate their children by modeling appropriate behavior and conveying positive attitudes: “Young children can mimic their parents and emulate what they observe. Hence, when parents demonstrate positive behavior and convey appropriate attitudes towards sexuality, their children will learn that.” (PS-02)

Several participants discussed the use of folktales and narratives to instill values related to sexual health education. One female participant shared the experience of using stories to promote sexual health awareness among her children: “There are short stories that you can share with children, which can benefit them, including ‘ tatsuniya ’ [folktales]. I typically provide them with ‘ tatsuniya ’ related to these topics.” (RS-03)

Media-Related Literacy

This subtheme reflects participants’ emphasis on the importance of parents’ and caregivers’ media literacy and promoting sexual health in children. A caregiver with media literacy can critically evaluate the information and messages about sexuality that children may encounter through various media sources such as television, the internet, and social media. They would also be able to guide children in understanding and interpreting these messages in a responsible and informed manner. However, one participant raised concerns regarding the lack of media literacy among parents, which results in parents’ negligence and inability to provide proper orientation: “Another problem is that parents often treat their children negligently by allowing them to do as they please without providing guidance. As a result, children may use media whenever and however they like, without limits.” (RS-03)

The concern about media literacy raised by most of the respondents highlights the need for parents to be aware of their children’s access to smartphones and media content. Negligence in guiding children’s media use can potentially lead to issues such as exposure to inappropriate content. This necessitates parents to guide their children on how to identify appropriate media content.

Ability to Develop Self-esteem and Assertiveness

Parents’ ability to instill courage in their children was emphasized, as it plays a crucial role in their future decision-making. Children who are valued and respected from an early age are less likely to follow orders blindly, whether from adults or peers. As one participant noted, “Parents’ ability to give their children courage is important because that will help them in the future. Some children are so unskilled that if an adult or even peer gives them an order, they will follow it, even if it is wrong. Sexual vulnerability starts from there.” (PS-01)

Theme 2. Adequacy of External Support

The educators argued that sexual health education is not solely an individualized aspect of education, and it should be addressed through an inter-sectoral collaboration, where different community sectors work together to solve a social problem. Recognizing this approach, participants suggested that interventions from the community, cooperation between homes and schools, the legal and punitive system, professionals, and religious practitioners can improve the quality of sexual health literacy within families, as depicted in Table 4.

Table 4.

Codes and Sub-themes Related to the Main Theme of “Adequacy of External Resource and Support”

|

Subthemes

|

Codes

|

| Advocating for a communal approach |

Collaborative monitoring |

| Collaborative response to social problems |

| Stronger involvement of the legal system |

Punishing sexual offenses and violations |

| Provision of legal support to victims of sexual offense |

| Professional intervention |

Public enlightenment and raising awareness |

| Responding to misconceptions and developing a positive attitude |

| Motivational intervention for parents |

| Enhancement of parenting skills |

| Home-school cooperation |

Basic educational support |

| Collaborative approach to emerging issues |

| Utilization of religious opportunities |

Involvement of religious scholars |

| Inclusion of the congruent religious content |

Advocating for a Communal Approach

The significance of social cooperation in addressing sexual issues has been recognized as crucial. Community members can assist by monitoring children’s activities and interactions and by supporting one another in addressing concerning behavior. However, as one religious scholar reiterated, the level of communal cooperation has declined compared to earlier times: “In the past, communal cooperation was stronger. A neighbor could discipline another neighbor’s child, and the other neighbor would express gratitude due to the belief that a child belongs to everyone. However, this situation has changed over time.” (RS-03)

A communal approach involves actively monitoring children’s activities by neighbors or other community members to ensure that educational issues are addressed for young children and youth, and deviant and destructive behaviors are prevented within the community.

Strengthening the Legal Framework

Participants emphasized the importance of a robust legal system in combating sexual offences. They cited legal action taken against harassers and assaulters, which they believe can serve as a deterrent. One educator stated: “Legislation also helps in reducing sexual biases. The former president approved a harassment bill, leading to some individuals being sentenced to imprisonment. Consequently, this has made others more cautious.” (ED-02)

Most participants agreed that addressing sexual offenses is crucial for preventing harm to children and adolescents. Others reported that some parents conceal the occurrence of sexual offenses due to stigma and shame. They emphasized the importance of not hiding instances of sexual abuse. They further stressed that reporting such cases to legal authorities and ensuring they are handled according to the law will help prevent their recurrence. A psychologist stated that “Taking action against sexual offenses is essential to prevent future occurrences. Some parents may attempt to conceal such incidents to safeguard their family’s reputation. Perpetrators of rape are sentenced to twenty-five years in prison, which often helps diminish the impact.” (PS-02)

However, this statement appears to conflict with Section 358 of the Criminal Code Act in Nigeria, which states that, “Any person who commits the offence of rape is subject to life imprisonment (not 25 years)” (source: https://jurist.ng/criminal_code_act/sec-358).

Professional Interventions

Some participants argued that a lack of sexual health literacy contributes to parental negligence, and suggested that professionals can play a role in raising awareness and addressing the existing misconceptions through various resources: One religious scholar asserted: “Professionals can help raise awareness and educate parents on the broader scope of sex education, including how it aligns with our religious beliefs.” (RS-03)

Most participants stressed the significance of parents understanding that sexual health education encompasses more than just sexual intercourse. It also promotes values and aims to strategically enlighten parents to cultivate a positive attitude by conducting open orientations and public presentations. A community health officer reported some instances of activities that can enlighten families saying that: “For example, in our health education sector, we use visual media, radio, leaflets [brochures], pamphlets, magazines, and posters. Posters are particularly helpful for those who are illiterate because they can interpret the content through pictures.” (HO-02)

Home-School Cooperation

Schools and other educational centers can support parents by providing essential educational resources for sexual health education. One participant mentioned that some schools offer programs to educate parents on various issues related to their children. However, there seems to be a lack of interest from some parents in participating in such programs: “In some schools, there are Parent Teacher Association [PTA] programs, some of which enlighten parents about their children’s sexual health, and they contribute considerably; however, not all parents attend.” (SO-01)

Participants stressed the importance of home-school cooperation in developing programs to educate and motivate parents. They highlighted the need to contact parents to raise their awareness of potential issues or risks concerning their children. This cooperation goes beyond mere participation in awareness programs, and it also requires active parental monitoring to identify and address emerging problems that could negatively impact their children.

Use of Religious Capacities

Most participants underscored the significance of incorporating religion, given its strong impact on individuals in the area. They recommended integrating religious teachings that align with the goals of sex education while cautioning against addressing topics that conflict with religious values. As one sociologist stated: “When considering the implementation of sex education in the northern region, it is important to acknowledge the significant influence of religious beliefs. Religion is deeply intertwined with our culture and cannot be overlooked in this context.” (SO-02)

While some participants advocate for the inclusion of religious teachings in sexuality education, others argued that relying solely on religious teachings can effectively address the needs related to sexuality, and it can be more supportive and cost-effective compared to a health-based and contraception-centered approach: “The majority of people in northern Nigeria are Muslim, so there is a concerted effort to adhere to Islamic principles regarding marriage and the upbringing of children. Consequently, issues related to moral decadence and sexual misconduct are less prevalent in the North due to the influence of Islam.” (ED-01)

This statement indicates that religious teachings provide specific guidance on marital life and child-rearing. These teachings emphasize sexual deviance, misconduct, and moral decadence, which the majority of respondents ay view as more important than health and rights-based issues.

Theme 3. Culturally Proportionate content

Participants emphasized the importance of sex education in promoting family-based sexual health education, which should align with cultural values and cover culturally appropriate topics. Respondents suggested some topics as culturally appropriate that can help individuals avoid engaging in offensive relationships or risky behaviors (Table 5).

Table 5.

Codes and Sub-themes Related to the Main Theme of “Culturally Proportionate Content”

|

Subthemes

|

Codes

|

| Hygienic procedure and disease prevention |

STI and HIV awareness |

| Proper toileting and bathing practices |

| Menstruation-related instructions |

| Religious ritual bath (for Muslims) |

| Sexual abuse prevention |

Instruction about interpersonal boundaries |

| Reporting abusive communication |

| Helping child to identify trusted elder |

| Teaching how to seek help when necessary |

| Gender-related orientation |

Gender roles and social values |

| Gender disparity awareness |

| Puberty education |

Pubertal signs and characteristics |

| Reproductive system awareness |

| Peer group relationship |

| Relationship with the opposite gender |

| Family rules and boundaries |

Bedroom rules and boundaries |

| Decent attire |

| Privacy rules |

| Chaste behavior |

| Abstinence and self-control |

Goal setting and engagement |

| Self-awareness |

| Decision-making skills |

Thoughtful consideration and consequence Anticipation |

| Internalization of values |

Note. STI: Sexually transmitted infection; HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus.

Hygienic Procedures and Disease Prevention

Educators stressed the importance of incorporating health education into sex education curricula to educate children about how to protect themselves against infections and diseases. By informing them about HIV and other potential health risks, the educators aim to ensure the sexual health of the students. A female sociologist made the following statements regarding this approach: “From the beginning, it is important to teach your daughter to maintain good hygiene, proper toileting practices, menstruation management, and, for Muslim girls, purification baths. Additionally, it is crucial to teach girls how to protect themselves.” (SO-02)

Sexual Abuse Prevention

Efforts to address sexual abuse and harassment were deemed essential measures to uphold the sexual health and well-being of the intended beneficiaries of sexual health education. Most participants shared specific guidelines that should be taught to children as part of this sexual health education. Respondents emphasized the importance of maintaining boundaries with strangers, seeking assistance in critical situations, recognizing trusted sources of help, and encouraging family members to report instances of abuse. As one female sociologist maintained: “Parents instruct their children not to follow strangers and not to accept gifts such as chocolate from them, as harassment can sometimes begin in that way.” (ED-03)

To protect children from sexual vulnerabilities, parents and caregivers can instruct them to report suspicious interactions to trusted elders, as explained by a participant who shared an example of parent-child communication on preventing sexual abuse: “…If anyone says something inappropriate to you, tell me or tell a neighbor. Report anyone who speaks to you in that manner.” (ED-01)

Gender-Related Orientations

Participants underscored the importance of addressing children’s perceptions of gender roles and guiding them on gender-appropriate activities as part of sexual health education. They further explained that certain roles should not be assigned to boys or girls to reduce the risk of sexual harassment. One participant suggested that sex education should focus on helping children understand their gender identity, their roles as boys or girls, and their various responsibilities in life. “Sexuality education is about helping children understand their gender, identity, and roles as girls or boys...” (ED-03)

In the case of gender roles, one participant expressed concern regarding the suppression of girls in some households, particularly in terms of limited access to education and early marriage, often leading to early pregnancy or parenthood. This concern was attributed to the dominant cultural beliefs and the perceived protective nature of such restrictions: “In every household, not all girls are granted the same level of freedom. In certain homes, girls are suppressed and denied the opportunity to attain a high level of education, except in more enlightened families.” (SO-02)

Pubertal and Reproductive Health Education

All participants asserted that sex education should include information about puberty and social interactions, as well as guidance on peer relationships, interactions with the opposite gender, and appropriate attire to prevent adolescents from experiencing early sexual debut. One participant highlighted the importance of explaining the signs of puberty and menstruation to children in a logical and calm manner, saying: “Then, she is instructed logically about the signs of puberty, like pubic and armpit hair growth. Here, parent should familiarize their children with mensuration blood, calm them down, and then explain puberty to them.” (HO-02)

Other participants stressed the need to educate adolescents about appropriate and inappropriate relationships as they reach puberty: “My understanding of sexuality education is to teach children how to relate to others. Moreover, when a girl reaches puberty, she should know that there are types of relationships that are appropriate, while others are not.” (SO-04)

According to the participating educators, parents play a crucial role in developing supportive communication with their children and providing them with proper information about maturity and responsibilities. By guiding their children through key topics such as puberty, menstruation, relationship boundaries, and the implications of certain actions, parents can promote sexual health and well-being in their children and help prevent risky sexual behaviors.

Family Rules

According to the participants, the primary concern regarding sexual matters extends beyond health and safety to include modesty and other cultural values. It was noted that children should be taught to respect privacy, dress appropriately, and understand bedroom boundaries: “Once children reach an age where they can understand [sexual matters], parents should ensure they have separate beds, teach them not to enter their parents’ room without permission, instruct them to stay away from occupied toilets or bathrooms, and establish other rules to help them understand the importance of respecting boundaries.” (SO-03)

One male educationist provided an example of how they trained their children to communicate their need for privacy when changing clothes, indicating their internalization of personal boundaries: “If their mom wants to change her clothes, she will shout from there, ‘No one should enter!’ and now our children (primary school students) have learned this.” (ED-03)

Abstinence and Self-control

Educators identified abstinence and self-control as essential components of sexual health education in northern Nigeria. They emphasized the necessity of teaching parents to safeguard children by instilling self-control and internalizing values of morality and chastity: “The method [of sexual health education] today is not the same as it was in the past. Hence, what we do now is, first of all, inculcate self-control and help them internalize the value of morality and chastity.” (RS-02)

Responsible Decision Making

Educators suggested decision-making as another content of sexual health education that can help individuals develop self-awareness and make responsible decisions. They emphasized educating children about responsible decision-making by providing guidelines and encouraging them to consider the potential consequences of their actions. One participant underscored the importance of promoting responsible decision-making through active interaction with children and encouraging them to engage in thoughtful consideration of behaviors and their consequences, rather than simply issuing orders: “Instead of giving orders, we need to train our children in a way that they can learn how to decide responsibly, by providing criteria and having them foresee the outcomes of their actions.” (ED-02)

Discussion

The primary focus of family-based sexual health education in northern Nigeria, as emphasized by the stakeholders, is to protect children from potential sexual offenses, prevent diseases and infections, discourage deviant and risky sexual behaviors, and promote responsible decision-making and abstinence. To achieve these goals, key informants identified three main facilitators. These facilitators align with the ecological systems theory, which suggests that individuals are influenced by a network of interconnected environmental systems, ranging from immediate surroundings (microsystem) to broader societal structures (macrosystem) (28). According to the theory, family-based sexual health education can be enhanced when necessary conditions are met at the individual, cooperative (mesosystem), and sociocultural levels (macrosystem). The microsystem, representing family and school settings, is considered the most influential part of the system and can be enhanced by the personal competence of caregivers.

This study revealed that parental and caregiver competence is the most crucial factor in promoting family-based sexuality education. Research by Asgharinekah et al (6), Emenike et al (11), and Torabi and Khosravi (29) support the idea that parents with higher sexual health literacy are better able to guide their children. For example, parents who actively monitor their children and engage in open discussions about sexual decisions and their consequences were found to promote positive behavioral changes (30). However, the research also uncovered deficiencies in parents’ attitudes and skills related to providing sexual health education. Similar limitations were noted in other studies, with some parents expressing concerns that discussing sexuality with their children may increase sexual activity, leading them to avoid such conversations (17). Furthermore, societal norms may make some children uncomfortable expressing their curiosity about sex, which may have negative consequences, as reported by Prinsloo and da Costa (31), who reported an increase in sexual offenses. Nevertheless, other findings indicated that many parents hold a positive attitude toward discussing sexuality with their children (17).

The observed weakness in parental competence highlights the need for collaboration between the family, as a microsystem, and other microsystems such as the schools and health centers to achieve better outcomes. Our research findings emphasize the importance of this interaction, known as the mesosystem in the ecological system theory. A communal approach can facilitate family-based sexual health literacy through cooperation between various members of society, including family, school staff, health professionals, legal authorities, and other community members. Likewise, other studies have documented the influence of this systemic approach (32,33). For example, Odimegwu and Mkwanazi (34) found that community coherence and connectedness were inversely associated with teenage pregnancy rates. Furthermore, the misconceptions and inadequacies in parenting skills reported by respondents can be resolved through system-wide and professional interventions. Such interventions should provide more effective educational content and procedures, as suggested by our findings and previous studies (6,11).

The research findings identified the cultural system (macrosystem) as a significant factor influencing ideology, attitude, and social conditions related to sexual health education. In northern Nigeria, the dominant cultural situation emphasizes abstinence and moral values as the primary objectives of sex education, similar to other African countries (35,36). This, in turn, affects the required content and process. According to the obtained data, resistance to the current curriculum does not reflect a rejection of sexual health education entirely. Rather, it highlights the need for a more culturally appropriate program for the targeted population. Some parents have been actively involved in providing sexual health information to their children by incorporating their cultural values. For instance, when teaching young adolescents about hygiene and reproductive health, they also encourage them to avoid close relationships with the opposite gender as a means of preventing risky and illicit sexual behaviors (17).

Family-based sexual health education in Nigeria appears to be abstinence-based in nature, prioritizing moral reasoning and self-control as measures of preventing measures against risky or deviant behavior, rather than teaching safe sex and contraceptive use. Our findings align with other studies that show parents in this region place more emphasis on abstinence and moral values (37,38), advocating delayed sex and self-control as more appropriate within the country’s cultural context. Some empirical studies have also demonstrated the effectiveness of abstinence and self-control (39,40). However, other studies that reported conflicting results argue that abstinence and delayed sex are not the best options (7,41).

Interestingly, the educator participants suggested that religious teachings should be incorporated into sexual health education, implying that religion was not seen as a barrier to implementing sexual health education in northern Nigeria, as reported in other studies (13,42). Instead, it was identified as a facilitating factor because it contains elements that can promote positive outcomes related to sexual health (43,44). This finding is consistent with Oluyinka’s study (45), which reported that religiosity was negatively associated with premarital sexual permissiveness in Nigeria, a pattern similarly reported by Paul et al (46) in another country. Religious teachings were found to be inherently compatible with many aspects of sex education (47,48). Many studies highlighting the restrictive effects of culture and religion on sex education fail to differentiate between religious content and the interpretation of that content by religious individuals, even though these two aspects are interdependent. However, there is a need to further explore the religious dimension and identify how values and scientific findings can be reconciled to ensure the provision of adequate sexual health literacy.

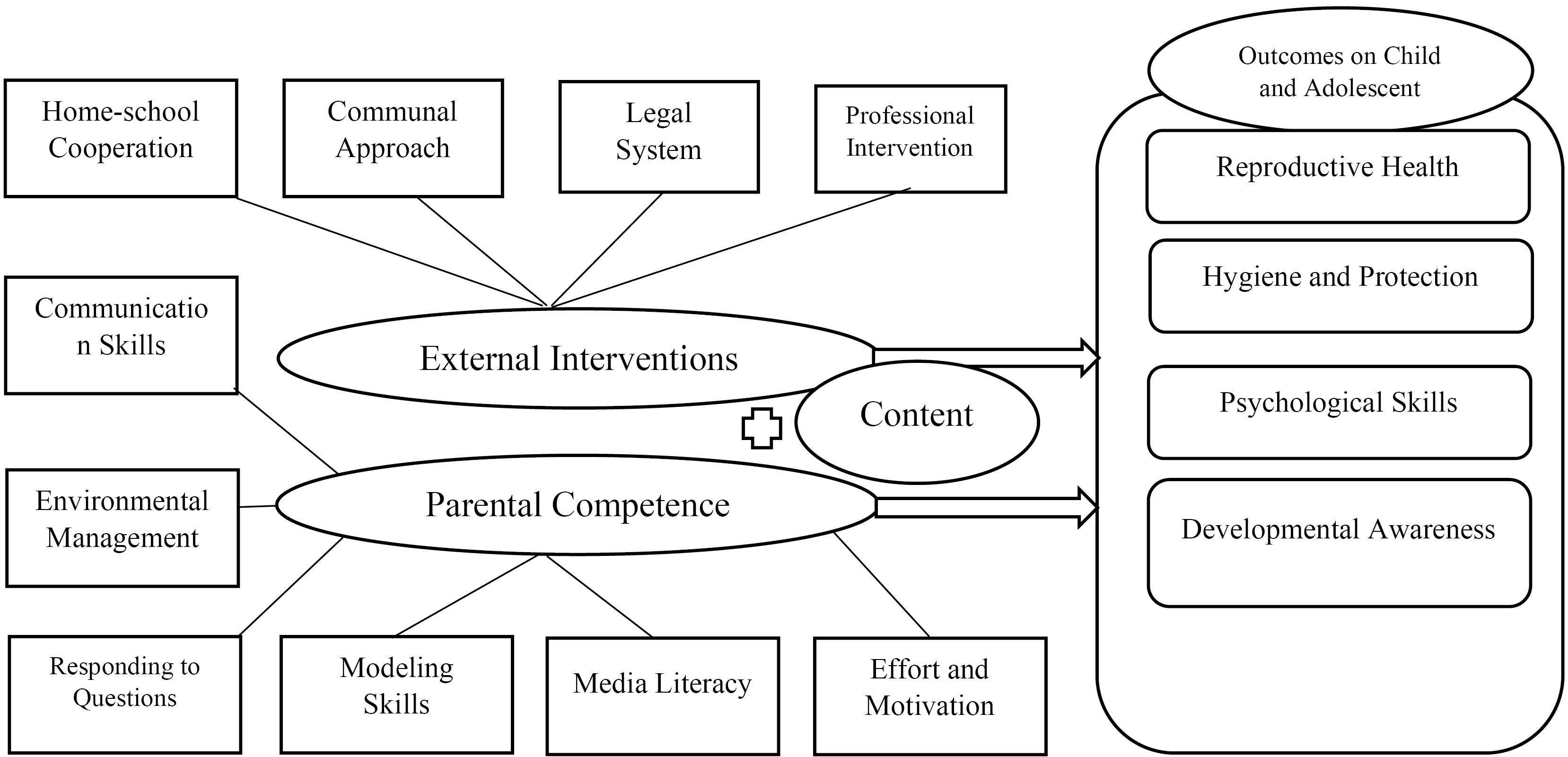

This study exclusively identified culturally appropriate content for sexual health education in northern Nigeria (Figure 1). It suggests that sex education is not solely cognitive. In addition to providing necessary information to children, home-based educational opportunities and community-based resources are utilized to develop essential skills. It also implies the necessity of exploring the components of an educational model that reconcile scientific findings and cultural values to respond to the family needs in the country.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Illustration of the Facilitating Factors of Sexual Health Literacy

.

Theoretical Illustration of the Facilitating Factors of Sexual Health Literacy

Conclusion

This study’s findings indicate that the family-based sexual health education approach adopted in northern Nigeria reflects a nuanced, multifaceted strategy aimed at promoting the overall well-being of children and young people. Importantly, this approach takes into account the cultural and religious contexts prevalent in the region, requiring educational models that can effectively reconcile scientific evidence with the cultural values and religious beliefs of local communities. This study suggests that family-based sexual health education can be tailored to deliver more meaningful and contextually appropriate outcomes for children and young people in the country.

Limitations and Recommendations

The study was restricted by sensitivities surrounding sexual matters in the region, resulting in a lack of access to some professionals to take part in interviews. Although our research has shed light on culturally appropriate content and the process of sexual health education in the region, it could not determine the extent to which cultural values converge with scientific evidence regarding the sex education process. Further studies are needed to provide more insight into the patterns of utilizing religious and cultural opportunities in the case of sexual health education. The findings underscore the urgent need for policy changes, improved training programs, and cultural involvement to effectively address deterrent challenges and promote sexual health within family settings. Additionally, there is a need to explore parents’ lived experiences in providing sexual health education to identify their instructional needs.

Authors’ Contribution

Conceptualization: Abubakar Salisu, Mahmood Saeedy Rezvani, Seyyed Mohsen Asgharinekah, Abdullahi Aliyu Dada, Hosein Kareshki.

Data curation: Abubakar Salisu.

Formal analysis: Abubakar Salisu.

Funding acquisition: Seyyed Mohsen Asgharinekah.

Investigation: Abubakar Salisu.

Methodology: Hosein Kareshki, Mahmood Saeedy Rezvani, Abubakar Salisu.

Project administration: Mahmood Saeedy Rezvani, Seyyed Mohsen Asgharinekah.

Resources: Abdullahi Aliyu Dada, Abubakar Salisu.

Software: Abubakar Salisu.

Supervision: Seyyed Mohsen Asgharinekah, Mahmood Saeedy Rezvani.

Validation: Mahmood Saeedy Rezvani, Abdullahi Aliyu Dada, Hosein Kareshki.

Visualization: Abubakar Salisu.

Writing–original draft: Abubakar Salisu.

Writing–review & editing: Abubakar Salisu, Mahmood Saeedy Rezvani.

Competing Interests

None.

Ethical Approval

This study is part of a doctoral thesis approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran (Approval ID: IR.UM.REC.1403.101). All participants provided informed consent to take part in the study, and the study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Funding

We received funding support from the Faculty of Education and Psychology, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran.

References

- Kempińska U, Malinowski JA. Risky sexual behaviour of adolescents as a worldwide problem–causes, effects and prevention. Issues Child Care Educ 2023; 617(2):3-15. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0016.2872 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Askari F, Mirzaiinajmabadi K, Saeedy Rezvani M, Asgharinekah SM. Sexual health education issues (challenges) for adolescent boys in Iran: a qualitative study. J Educ Health Promot 2020; 9:33. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_462_19 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bell SO, Omoluabi E, OlaOlorun F, Shankar M, Moreau C. Inequities in the incidence and safety of abortion in Nigeria. BMJ Glob Health 2020; 5(1):e001814. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001814 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Agege EA, Nwose EU, Nwajei SD, Odoko JE, Moyegbone JE, Igumbor EO. Epidemiology and health consequences of early marriage: focus on Delta State Nigeria. Int J Community Med Public Health 2020; 7(9):3705-10. doi: 10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20203948 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Heller JR, Johnson HL. What are parents really saying when they talk with their children about sexuality?. Am J Sex Educ 2010; 5(2):144-70. doi: 10.1080/15546128.2010.491061 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Asgharinekah SM, Sharifi F, Amel Barez M. The need of family-based sexual education: a systematic review. J Health Lit 2019; 4(3):25-37. doi: 10.22038/jhl.2019.14346 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pop MV, Rusu AS. The role of parents in shaping and improving the sexual health of children–lines of developing parental sexuality education programmes. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2015; 209:395-401. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.210 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Goldman JD. Responding to parental objections to school sexuality education: a selection of 12 objections. Sex Educ 2008; 8(4):415-38. doi: 10.1080/14681810802433952 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bersamin M, Todd M, Fisher DA, Hill DL, Grube JW, Walker S. Parenting practices and adolescent sexual behavior: a longitudinal study. J Marriage Fam 2008; 70(1):97-112. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00464.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Simovska V, Kane R. Sexuality education in different contexts: limitations and possibilities. Health Educ 2015; 115(1):2-6. doi: 10.1108/he-10-2014-0093 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Emenike NW, Onukwugha FI, Sarki AM, Smith L. Adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health education: perspectives from secondary school teachers in Northern Nigeria. Sex Educ 2023; 23(1):66-80. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2022.2028613 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Onukwugha FI, Magadi MA, Sarki AM, Smith L. Trends in and predictors of pregnancy termination among 15-24 year-old women in Nigeria: a multi-level analysis of demographic and health surveys 2003-2018. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020; 20(1):550. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03164-8 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mukoro J. Sex education in Nigeria: when knowledge conflicts with cultural values. Am J Educ Res 2017; 5(1):69-75. doi: 10.12691/education-5-1-11 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Izugbara CO. Home-based sexuality education: Nigerian parents discussing sex with their children. Youth Soc 2008; 39(4):575-600. doi: 10.1177/0044118X07302061 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Haberland N, Rogow D. Sexuality education: emerging trends in evidence and practice. J Adolesc Health 2015; 56(1 Suppl):S15-21. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.013 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Izadirad H, Zareban I. The relationship of health literacy with health status, preventive behaviors and health services utilization in Baluchistan, Iran. J Educ Community Health 2015; 2(3):43-50. doi: 10.20286/jech-02036 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Atenchong N, Oluwasola T. Provision of sex-related education to children in camps for internally displaced people in Benue state, Nigeria: mothers’ attitudes and practices. Sex Educ 2024; 24(3):433-44. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2023.2195162 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lee EM, Kweon YR. [Effects of a maternal sexuality education program for mothers of preschoolers]. J Korean Acad Nurs 2013; 43(3):370-8. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2013.43.3.370.[Korean] [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ozgun SY, Capri B. The effect of sexuality education program on the sexual development of children aged 60-72 months. Curr Psychol 2023; 42(9):7125-34. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02040-8 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wight D, Fullerton D. A review of interventions with parents to promote the sexual health of their children. J Adolesc Health 2013; 52(1):4-27. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.04.014 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Nadeem A, Cheema MK, Zameer S. Perceptions of Muslim parents and teachers towards sex education in Pakistan. Sex Educ 2021; 21(1):106-18. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2020.1753032 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wright MF, Wachs S. The buffering effect of parent social support in the longitudinal associations between cyber polyvictimization and academic outcomes. Soc Psychol Educ 2021; 24(5):1145-61. doi: 10.1007/s11218-021-09647-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Frank K, Sandman L. Parents as primary sexuality educators for adolescents and adults with Down syndrome: a mixed methods examination of the Home BASE for intellectual disabilities workshop. Am J Sex Educ 2021; 16(3):283-302. doi: 10.1080/15546128.2021.1932655 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Aham-Chiabuotu CB, Aja GN. “There is no moral they can teach us”: adolescents’ perspectives on school-based sexuality education in a semiurban, southwestern district in Nigeria. Am J Sex Educ 2017; 12(3):315-36. doi: 10.1080/15546128.2017.1280442 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mukoro J. The need for culturally sensitive sexuality education in a pluralised Nigeria: but which kind?. Sex Educ 2017; 17(5):498-511. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2017.1311854 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ary D, Jacobs LC, Sorensen Irvine CK, Walker D. Introduction to Research in Education. 9th ed. Wadsworth: Cengage Learning; 2014. p. 723.

- Cresswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 2nd ed. SAGE Publications; 2007.

- Darling N. Ecological systems theory: the person in the center of the circles. Res Hum Dev 2007; 4(3-4):203-17. doi: 10.1080/15427600701663023 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Torabi F, Khosravi A, Zolfagharnasab Hajizadeh A, Nemati-Anaraki L, Jafari Pavarsi H, Hashemian A. The relationship between the levels of sexual health literacy of parents and their adolescent. J Health Lit 202; 8(2):87-93. [ Google Scholar]

- Changizi M, Mohamadian H, Cheraghian B, Maghsoudi F, Shojaeizadeh D. Health literacy predicts readiness to behavior change in the Iranian adult population. J Health Lit 2023; 7(4):84-92. doi: 10.22038/jhl.2022.66181.1312 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Prinsloo J, da Costa G. Exploring the personal and social context of female youth sex offenders. J Psychol Afr 2017; 27(5):452-4. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2017.1379658 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kismödi E, Cottingham J, Gruskin S, Miller AM. Advancing sexual health through human rights: the role of the law. Glob Public Health 2015; 10(2):252-67. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.986175 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ngwibete A, Ogunbode OO, Mangalu MA, Omigbodun A. Displaced women and sexual and reproductive health services: exploring challenges women with sexual and reproductive health face in displaced camps of Nigeria. J Educ Community Health 2023; 10(3):162-72. doi: 10.34172/jech.2612 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Odimegwu C, Mkwananzi S. Family structure and community connectedness: their association with teenage pregnancy in South Africa. J Psychol Afr 2018; 28(6):479-84. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2018.1544390 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- de Haas B, Hutter I. Teachers’ conflicting cultural schemas of teaching comprehensive school-based sexuality education in Kampala, Uganda. Cult Health Sex 2019; 21(2):233-47. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2018.1463455 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Helleve A, Flisher AJ, Onya H, Mukoma W, Klepp KI. South African teachers’ reflections on the impact of culture on their teaching of sexuality and HIV/AIDS. Cult Health Sex 2009; 11(2):189-204. doi: 10.1080/13691050802562613 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Esan DT, Bayajidda KK. The perception of parents of high school students about adolescent sexual and reproductive needs in Nigeria: a qualitative study. Public Health Pract (Oxf) 2021; 2:100080. doi: 10.1016/j.puhip.2021.100080 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Esohe KP, PeterInyang M. Parents perception of the teaching of sexual education in secondary schools in Nigeria. Int J Innov Sci Eng Technol 2015; 2(1):89-99. [ Google Scholar]

- Quinn PD, Fromme K. Self-regulation as a protective factor against risky drinking and sexual behavior. Psychol Addict Behav 2010; 24(3):376-85. doi: 10.1037/a0018547 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rabbitte M. Sex education in school, are gender and sexual minority youth included?: A decade in review. Am J Sex Educ 2020; 15(4):530-42. doi: 10.1080/15546128.2020.1832009 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mudhovozi P. Unsafe Sexual Behavior, Reasons for Consequences and Preventive Methods Among College Students. J Psychol Afr 2011; 21(4):573-5. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2011.10820499 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dienye VU. The educational and social implications of sexuality and sex education in Nigerian schools. Afr J Soc Sci 2011; 1(2):11-9. [ Google Scholar]

- Askari F, Mirzaiinajmabadi K, Saeedy Rezvani M, Asgharinekah SM. Facilitators of sexual health education for male adolescents in Iran: a qualitative study. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 2020; 25(4):348-55. doi: 10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_299_19 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Le Gall A, Mullet E, Rivière Shafighi S. Age, religious beliefs, and sexual attitudes. J Sex Res 2002; 39(3):207-16. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552143 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Oluyinka OA. Premarital sexual permissiveness among Nigerian undergraduates: the influence of religiosity and self-esteem. J Psychol Afr 2009; 19(2):227-30. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2009.10820283 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Paul C, Fitzjohn J, Eberhart-Phillips J, Herbison P, Dickson N. Sexual abstinence at age 21 in New Zealand: the importance of religion. Soc Sci Med 2000; 51(1):1-10. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00425-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Aftab Khan M, Hussein Rasool G, Mabud SA, Ahsan M. Sexuality Education from an Islamic Perspective. Cambridge Scholars Publishing; 2020.

- Tabatabaie A. Childhood and adolescent sexuality, Islam, and problematics of sex education: a call for re-examination. Sex Educ 2015; 15(3):276-88. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2015.1005836 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]